Introduction

In contrast to Asian countries, in Western Europe the incidence of gastric cancer is declining. Still, at number 5 for men and 6 for women it is among the most common forms of cancer. Moreover, largely due to its still poor overall prognosis (5-year-survival rate of 20% to 30%) it remains one of the most common causes of death from malignancy. Treatment strategies today are based a multimodality concept in which visceral surgery plays the major role. In Japan the incidence of gastric cancer is 5 times higher than in the West. In response, Japan has developed very good screening programs that reliably detect early forms of gastric cancer and have led to a clearly higher incidence of early gastric cancers. Such a screening program would not be practicable in Germany due to the much lower incidence of gastric cancer; it is also not recommended in the S3 guidelines.

Localization

Gastric carcinomas are classified according to whether they are located in the distal third, the middle third, or the proximal third of the stomach. The latter are currently increasing in incidence, but the most frequent localization is the distal third (Antrumbereich).

Adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction (AEG) are divided in the AEG classification into adenocarcinomas of the distal esophagus (AEG type I), true carcinomas of the cardia (AEG type II) and subcardial carcinomas (AEG type III). The classification plays a key role in the choice of surgical procedure on the extent of the resection. AEG III tumors require a gastrectomy, AEG II tumors a transhiatal extended gastrectomy, and AEG I tumors esophageal resection.

Macroscopy

Based on macroscopic appearance, gastric carcinomas are divided according to the Borrmann classification into 4 types, which play however a rather subordinate clinical role.

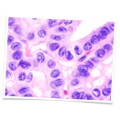

Histology

More important is the their histological classification. The WHO classification distinguishes 8 different types, of which adenocarcinomas comprise the overwhelming proportion. The classification of Laurén was introduced in 19651. It makes a distinction according to the main histological types of gastric carcinoma, namely intestinal and diffuse.

Differentiation

Finally, gastric carcinomas can be classified into 4 types according to their differentiation, G1=well differentiated, G2=moderately differentiated, G3=poorly differentiated, and G4=undifferentiated.

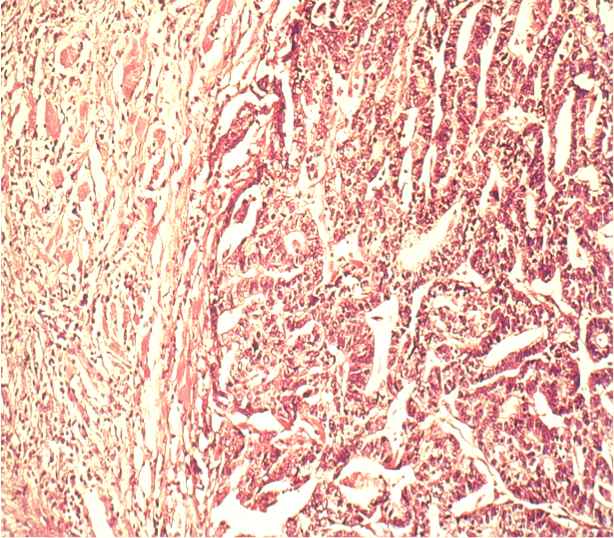

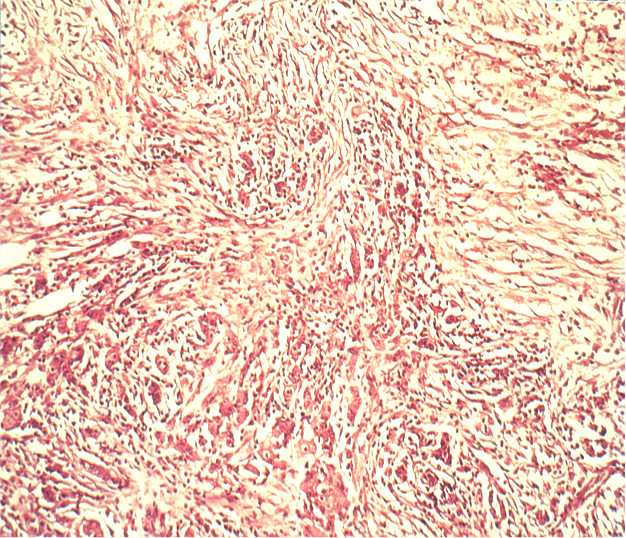

Intestinal Type

The intestinal type of gastric carcinoma is generally macroscopically well defined, tends to grow continuously, and has a gland-like differentiated appearance under the microscope that resembles intestinal mucosa. Because this type occurs preferentially in certain age groups and regions, it is also called the epidemic type of gastric carcinoma.

Diffuse Type

Because this type is influenced more by genetic factors than by lifestyle it is also known as an endemic type. It is macroscopically harder to demarcate and shows a diffuse histological growth pattern with widely disseminated tumor cells. Because of the diffuse spread, it is difficult to reliably distinguish the tumor margins macroscopically, making it imperative to maintain a wider safe resection margin.

Etiology

Risk factors for gastric carcinoma include chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori, chronic atrophic gastritis, type A, high dietary nitrite intake (with gastric acid-catalyzed formation of nitrosamine), gastric ulcer, and prior gastric surgery (gastric stump carcinoma status following Billroth II resection). The suspicion that certain dietary habits increase the risk of gastric cancer is supported by the observation of Japanese emigrants to Western countries. If they adopt Western dietary habits, their risk of gastric carcinoma drops dramatically, if they retain their customary diet in their new homes, the incidence remains high.

A rare precancerous condition is Ménétrier disease, or hypoproteinemic hypertrophic gastropathy, which is often accompanied by H. pylori infection and which progresses to gastric carcinoma in 10% of patients.

Symptoms

The complete lack of early symptoms makes timely recognition of gastric carcinoma enormously difficult. Early symptoms are the exception and usually constitute incidental findings. Unspecific epigastric pain should therefore always be differential diagnostically clarified by endoscopy, which is highly sensitive for gastric carcinoma. Patients with one or more of the following alarm symptoms clinically associated with suspected esophageal or gastric carcinoma should be referred to early endoscopy with extraction of biopsies:

- Dysphagia

- Recurrent vomiting

- Inappetence

- Weight loss

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

AEG Classification

Adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction (AEG) are divided in the AEG classification into adenocarcinomas of the distal esophagus (AEG type I), true carcinomas of the cardia (AEG type II) and subcardial carcinomas (AEG type III). The classification plays a key role in the choice of surgical procedure on the extent of resection. AEG III tumors require a gastrectomy, AEG II tumors a transhiatal extended gastrectomy, and AEG I tumors esophageal resection.

Diagnostik

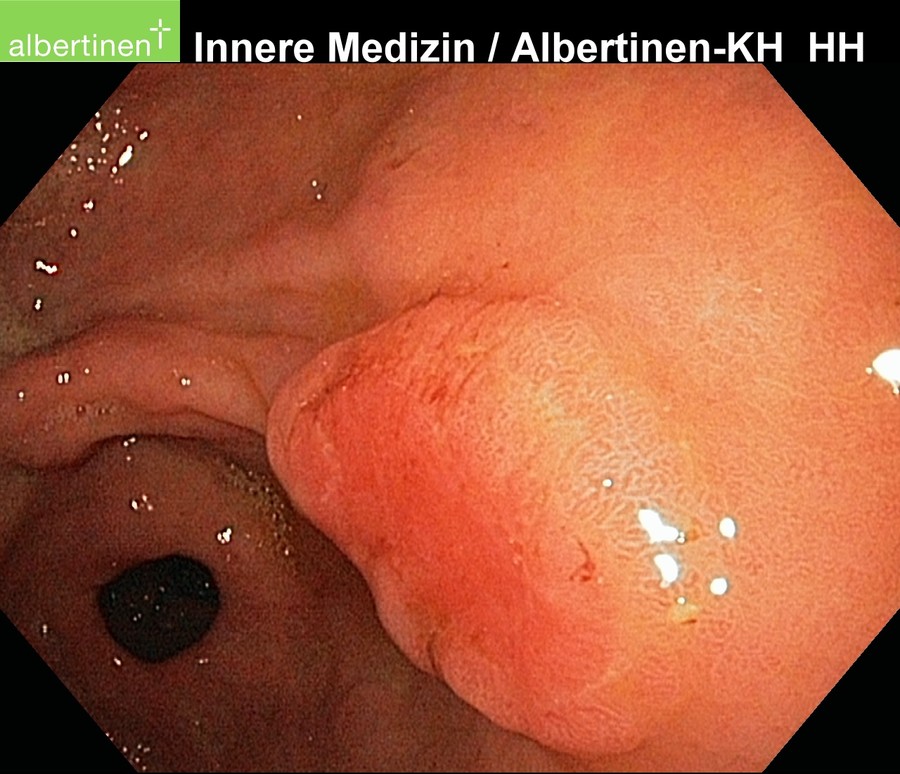

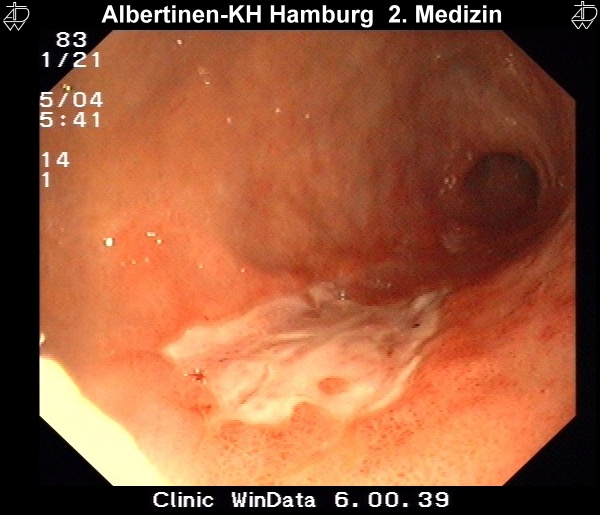

Endoscopy

The examination method of choice is endoscopy. It allows macroscopic and histological diagnosis as well as reliable tumor localization. Supplemental endoscopic ultrasound can be used for local assessment of the extent of spread. More difficult to evaluate by endoscopic ultrasound is the regional lymph node metastatic spread.

by courtesy of Albertinen-Krankenhaus in HamburgSonography

Perkutaneous sonography of the neck in gastric cancer can be performed to rule out lymphatic metastasis. In AEG-II-tumors it should be undertaken regularly in addition to other staging examinations. At the junction of the thoracic duct in the left subclavian vein, a lymphnode metastasis can be present. It is then called "Virchow-Lymphnode"

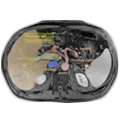

Staging

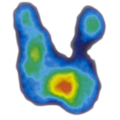

The extent of gastric carcinoma spread is evaluated by endoscopy with tissue removal for biopsy, and CT (Schnittbildgebung) of the thorax and abdomen. CT can confirm or exclude distant metastases. Endosonography can assess depth the tumor penetration in the gastric wall layers.

It can also detect possible lymph node metastases. In individual cases, PET scan can help to clarify suspicious masses, e.g. whether a metastasis is present in the liver.

Staging Laparoscopy

Gastric carcinoma metastasis occurs along hematogenous and lymphogenous pathways as well as per continuitatem in the form of peritoneal carcinomatosis. This is difficult to recognize in CT images, especially if they are present in limited extent. The presence of a peritoneal carcinomatosis, however, is of major importance for therapy since curative resection is then usually no longer possible and the patient can be spared a laparotomy.

Palliative resection should not be performed for gastric carcinoma unless rendered necessary by an obstruction refractive to treatment or by bleeding. Staging laparoscopy can exclude a peritoneal carcinomatosis before gastrectomy. It can also disclose previously overlooked liver metastases and obtain peritoneal wash cytology (PWC) specimens.

The finding of malignant cells in PWC correlates with a poor prognosis, but does not change treatment. If a peritoneal carcinomatosis is present in gastric carcinoma then, depending on the circumstances, intraoperative hyperthermal intraabdominal chemoperfusion (HIPEC) can be performed. For this situation, several studies have described the use of a neoadjuvant approach with intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

No evidence supports the use of tumor markers. Numerous studies have investigated the importance of markers ranging from known markers like carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen (Ca)19–9 and Ca72–4, to novel markers that may also provide clues of tumor metabolism or pathophysiological changes in the stomach related to carcinogenesis (pepsinogen). For none of these markers are the reported sensitivity and specificity adequate for primary diagnosis, which renders them unsuited as tools for screening or staging. The barium meal test is also not appropriate for staging of tumors of the stomach or esophagogastric junction. The localization of the tumor can be determined by endoscopy and CT reconstruction techniques.

Interested in current diagnostic and treatment standards in Germany for gastric carcinoma? Then read the evidence-based

S3-guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of gastric carcinoma.

Therapy

The decisive factor in treatment of gastric carcinoma that most dramatically impacts overall prognosis is surgery. The goal here is always to achieve an R0 resection, i.e. a resection macroscopically and microscopically im Gesunden leaving no residual tumor in the body.

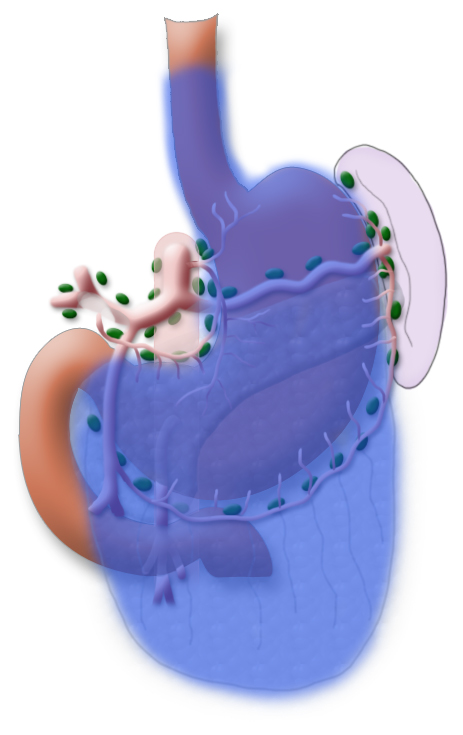

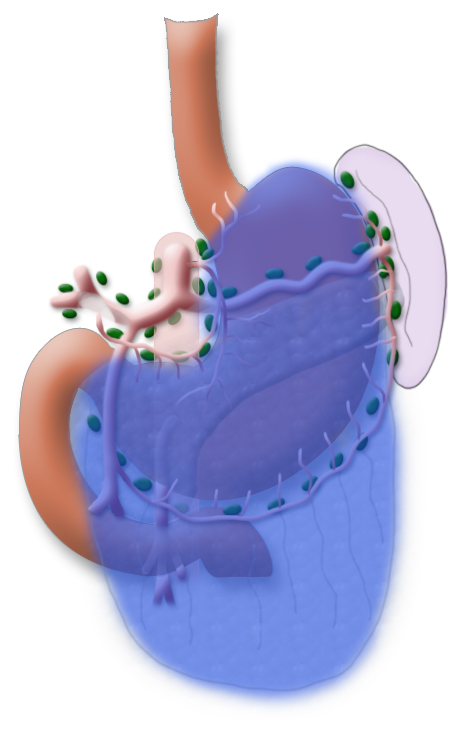

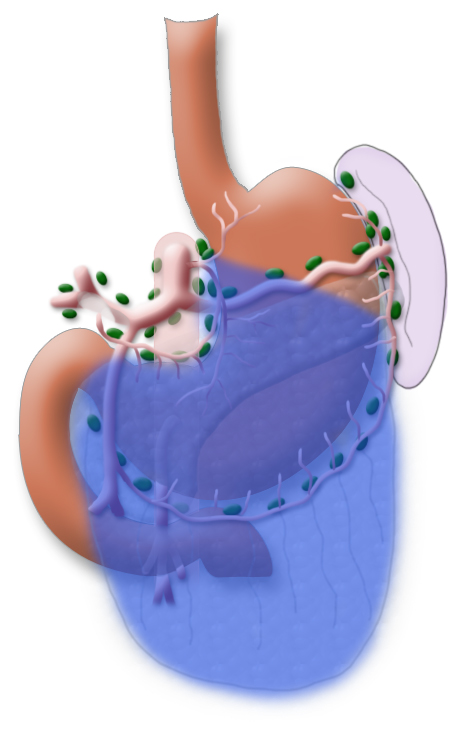

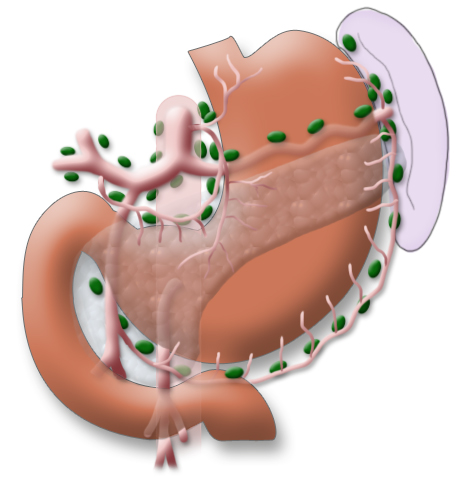

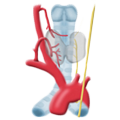

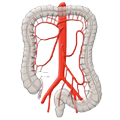

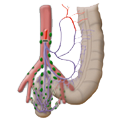

The gastrectomy is supplemented by removal of all lymph nodes directly surrounding the stomach (D1 segment) and along the truncus coeliacus, the hepatic artery, and the splenic artery (A. lienalis) (D2 segment). In Japan it is standard to perform an extended lymphadenectomy encompassing the D3 (DIII) segment.

This practice is based on the fact that Asian patients have less visceral fat, which also makes this step technically more simple. Metastases in the paraaortal and mesenteric lymph nodes (D3 segment) are judged to be distant metastases, their resection offers no advantage with regard to overall survival but does increase the procedure’s morbidity.

Risk Evaluation

The preconditions for successful surgery are resectability of the tumor and operability of the patient, i.e. the functional operability. Patients with gastric carcinoma are often under- or malnourished, which can have a major impact on postoperative outcome and development of e.g. anastomotic insufficiency. The patient’s overall physical capacity and comorbidities must also be taken into account.

Multimodality Therapy Concepts

In locally advanced tumors (uT3/uT4) neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be used to achieve tumor downsizing and downstaging and thus increase the chances of an R0 resection. After conclusion of prior chemotherapy, a re-staging examination is usually performed to assess the tumor’s response to treatment. Even if the response is good, subsequent resection is obligatory since the rare case of a complete response can only be established on a histologic specimen by a pathologist.

Surgical Resection

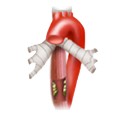

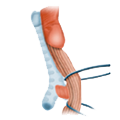

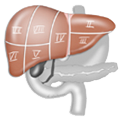

The location of the tumor and its histological type according to the Laurén classification affect the choice of surgical procedure. AEG-II tumors of the cardia are treated by extended transhiatal surgery in which the complete stomach and the distal part of the esophagus are resected. In gastric carcinoma it is standard to perform a gastrectomy.

Only in intestinal tumors located very far distally can subtotal or 4/5 gastric resection be carried out, provided care is taken to provide an adequate safe resection margin. This does not affect overall survival , but the quality of life after subtotal gastric resection is clearly better.2

An obligatory component of every gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma is omentectomy, i.e. removal of the membranous double layer of fatty tissue that has its evolutionary origin in the stomach. A bursectomy is also carried out, i.e. resection of the bursa omentalis on the pancreatic surface.

OP Video Gastrectomy

Here is a video of the entire procedure step-by-step. Shown is an oncological gastrectomy with omentectomy, bursectomy, systematic DII lymphadenectomy with simultaneous cholecystectomy and reconstruction of the esophagus (Passage) as terminolateral esophagojejunostomy with Herfarth-Lawrence-Rondino pouch.

1 Positioning & Overview

Preparation for gastrectomy, positioning of the patient

2 Access

Access to the abdominal cavity

- Access is gained through an upper abdominal transverse laparotomy; for orientation the costal arches are indicated on the skin with a marker.

- The anterior rectus sheath is opened

- The rectus abdominis muscle is dissected

- After opening of the peritoneum, the surgeon locates the round ligament of the liver and severs it between two Overholt forceps. This is done so that the supposedly obliterated vessels in this ligament can be opened again if portal hypertension develops.

3 Exploration

Exploration of the site, exposure of the tumors, exclusion of a peritoneal carcinomatosis

4 Omentectomy Part 1

Start of omentectomy

5 Hepatoduodenal ligament

Dissection of the hepatoduodenal ligament and right gastric artery

6 Omentectomy Part 2 and Bursectomy

Completion of the omentectomy and resection of the bursa omentalis

7 Dissection of the right gastro-omental artery

- The left gastroepiploic vascular arc is dissected, the vein is tied off, then the artery

8 Transsection of the duodenum

- The duodenal stump is carefully oversewed to prevent duodenal stump insufficiency, a feared complication, since it allows leakage of gall and pancreas secretions into the abdominal cavity

9 Lymphadenectomy truncus coeliacus, severing of the left gastric artery

- The lymphadenectomy is continued along the common hepatic artery

- The vena coronaria ventriculi is ligated

- The splenic artery is exposed, the left gastric artery is ligated and severed

- The surgeon now has an unimpeded view of the celiac trunk and aorta

10 Anatomic presentation following dissection in the area of the celiac trunk

- The entire course of the common hepatic artery is mobilized

- Lymphadenectomy in the area of the porta hepatis and the upper margin of the pancreas is concluded

- The celiac trunk lies exposed

- Further lymphadenectomy is performed along the splenic artery

11 Dissection of the short gastric arteries, continuation of the lymphadenectomy

- The greater omentum is detached along the greater curvature

- Lymphadenectomy along the splenic artery is continued up to the splenic hilum, taking care to preserve the pancreas

- The short gastric arteries are severed

12 Anatomic presentation following dissection of the short gastric arteries

13 Dissection of the esophageal hiatus

- To allow absetzen of the resected distal esophagus tissue, the esophageal hiatus must be mobilized

- The peritoneum of both crura of the diaphragm is incised

- The vagus nerve is exposed and severed with electrical scissors

- Finally the distal esophagus is completely mobilized

14 Resection, presentation of the specimen

- To allow later esophagojejunostomy for reconstruction of the esophagus (Passage), a circular stapler is introduced into the distal esophagus

- To affix this a purstring suture clamp is used to create a tobacco-pouch suture

- A clip is placed up to the resected tissue so that none of the stomach contents can escape, the resected tissue is dissected with scissors

- The resected tissue comprises the entire stomach, the greater omentum, and the removed lymph nodes

15 Anastomosis Part 1

- The purstring suture clamp is removed

- The esophagus is predilated, then the head of a 25mm circular stapler is placed into the esophagus and the purstring suture tied

- The upper part of the anastomosis is now prepared

16 Preparation for Reconstruction

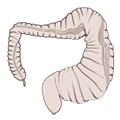

- For reconstruction of the esophagus (Passage) a jejunal loop is used

- The mesentery is dissected and skeletonized, preserving the central vascular arc

- The bowel is severed with a linear stapler

17 Mesocolic Pull-up of the Alimentary Loop

- To pull-up the small bowel loop for reconstruction, a transmesocolic window is created

18 Simultaneous Cholecystectomy

- IGastrectomy should always be accompanied by simultaneous cholecystectomy

- Not for oncologic reasons, but to avoid later complications caused by gall stones. The occurrence of gall stones is more likely after gastrectomy, and should they develop and become lodged in the bile duct after gastrectomy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can no longer be performed

- Simultaneous cholecystectomy does not increase the morbidity of the surgery

19 Pouch Formation

- If the anastomosis has to be placed in the thorax, there is not enough room to build a pouch

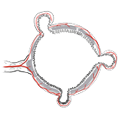

- The pouch consists of a duplication of the small bowel, which is formed into a lumen using a stapler

- Next a jejunal plication is placed around the pouch to provide some protection against reflux.

20 Esophagojejunostomy

- Esophagojejunostomy is performed with a 25mm circular stapler

- The stapler is inserted through the pouch and the central anvil punched through the bowel wall

- The stapler is then linked with the in stapler head in the esophagus and the anastomosis is being fired

- Two anastomosis rings are thus created, the proximal ring is usually sent for histological confirmation since it is the margin of resected tissue located furthest oral

21 Closing the Pouch

- After removal of the circular stapler the pouch is sutured closed

22 Evaluating Watertightness

- To evaluate the primary watertightness of the anastomosis, a stomach probe is introduced by the anesthesiologist

- It is positioned in the pouch, the small bowel is clamped shut and the pouch filled with a methylene blue saline solution

23 Sleeve Placement

- This jejunal plication is closed centrally with nonresorbable sutures, thus also protecting the anastomosis

24 Attaching the Alimentary Loop

- To prevent slippage of the alimentary loop, it is attached with resorbable sutures at the site where it emerges through the mesocolon

25 Jejuno-jejunostomy

- Reconstruction also includes a Roux-en-Y anastomosis

- Here the biliopancreatic loop meets the alimentary loop, i.e. bile and pancreatic juice meet partially digested food

- The anastomosis is laid end-to-side in hand suture technique

26 Closure of the mesocolon incision

To avoid an internal hernia, the mesocolon incision is closed with a continuous resorbable suture

27 Conclusion of the OP

Placement of drains ends the procedure. A Robinson drain is placed at the anastomosis, another in the area of the duodenal stump. The procedure ends with layered closure of the abdominal wall.

Lymphadenectomy

A systematic DII lymphadenectomy encompasses the removal of all perigastric lymph nodes and the nodes surrounding the celiac trunk, the hepatic artery, and the splenic artery. Usually more than 25 lymph nodes are removed and examined histologically. To achieve “pN0” in subsequent tumor staging, at least 16 regional lymph nodes should be examined and classified as tumor free. The spleen is not as a rule resected.3

Reconstruction

Restoration of intestinal continuity is done by pull-up of a small bowl loop. Patients experience improved swallowing function and quality of life if the small bowel loop is doubled to create a so-called pouch. A pouch however cannot be created intrathoracally, so this option is not available for AEG-II tumors.

If the patient is not functionally operable, definitive radiochemotherapy with curative intent can be administered. Otherwise perioperative chemotherapy, i.e. applied before and after surgery, is the standard procedure for advanced tumors. Preoperative radiochemotherapy is not indicated for gastric carcinoma.

Early Gastric Carcinoma

Early gastric carcinoma invades only the mucosa and submucosa. The Japanese classification differentiates between slightly raised (erhabenen), flat, and depressed types. Because of the excellent lymphatic drainage (Versorgung) of the submucosa, progression of the infiltration from the mucosa to the submucosa increases the probability of lymph node metastases from 4% or 5% to 22%. Early gastric carcinoma can be treated by endoscopic resection if the following criteria are met:

- Lesions <2 cm in slightly raised type

- Lesions <1cm in flat type

- No macroscopic ulceration

- Histological differentiation stage well or moderate (G1/G2)

- Invasion limited to the mucosa

Resection should be performed in a center with ample experience with the procedure. The resection should be en-bloc, which also allows for complete histological evaluation of the tumor margins.

Wound Healing

Wound Healing Infection

Infection Acute Abdomen

Acute Abdomen Abdominal trauma

Abdominal trauma Ileus

Ileus Hernia

Hernia Benign Struma

Benign Struma Thyroid Carcinoma

Thyroid Carcinoma Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism Hyperthyreosis

Hyperthyreosis Adrenal Gland Tumors

Adrenal Gland Tumors Achalasia

Achalasia Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal Carcinoma Esophageal Diverticulum

Esophageal Diverticulum Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal Perforation Corrosive Esophagitis

Corrosive Esophagitis Gastric Carcinoma

Gastric Carcinoma Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic Ulcer Disease GERD

GERD Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric Surgery CIBD

CIBD Divertikulitis

Divertikulitis Colon Carcinoma

Colon Carcinoma Proktology

Proktology Rectal Carcinoma

Rectal Carcinoma Anatomy

Anatomy Ikterus

Ikterus Cholezystolithiais

Cholezystolithiais Benign Liver Lesions

Benign Liver Lesions Malignant Liver Leasions

Malignant Liver Leasions Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis Pancreatic carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma