Epidemiology

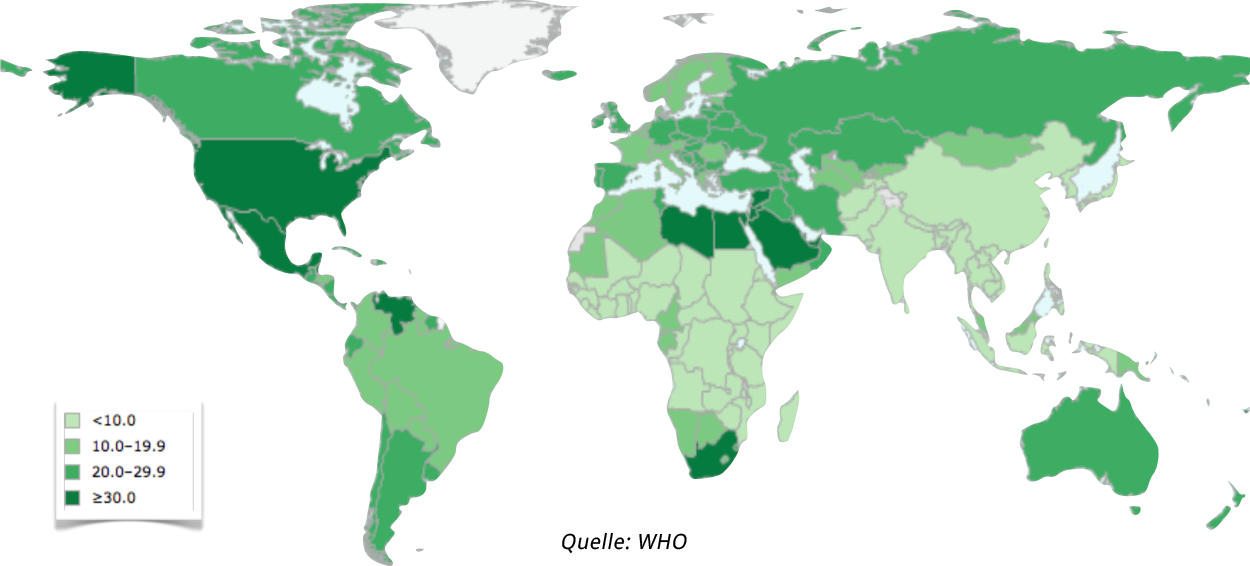

The proportion of adipose people is increasing dramatically worldwide. It can now be termed with justice a full-blown epidemic- or even pandemic-like spread. According to current WHO data, 21.3% of the German population are adipose, i.e. they have a BMI >30 kg/m2.

A BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more is termed grade II obesity, a BMI >40 kg/m2 as grade III obesity. The effects of obesity on health are dramatic, with numerous associated disorders, mainly diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. But various types of cancer are also more common in the obese.

There is also the massive economic impacts of higher health costs and time lost due to illness. For the individual, morbid adiposity usually means a dramatic decline in quality of life, social isolation, and encounters with prejudice. The often well-meant advice „Eat less and exercise more“, which every obese person certainly hears, ignores the fact that while it may prevent obesity, it certainly will not cure it. Someone who is so overweight that they suffer from exertional dyspnea and pronounced joint pain or degeneration, is limited in their ability to “exercise more”.

We live in a society that is increasingly sedentary, where hard physical labor is rare, and cheap calorie-rich food readily available and aggressively advertised. All this contributes to the steep rise in obesity that has occurred in almost all industrial -- but also emerging -- economies since the 1970’s.

Because conservative therapy is ineffective in the majority of patients, surgical procedures have been developed that alter the anatomy and physiology of dietary intake in such a manner that rapid and lasting weight loss is now possible.

In the United States of America, who are manifestly ahead of us in this development, surgery in morbidly obese patients has increased to such an extent that it has overtaken gallbladder and hernia operations as the most common surgical procedure. In Europe too such procedures are becoming ever more common.

Preconditions

Surgery to reduce pathological obesity represents a major encroachment on the patient’s anatomy and physiology and has a decisive influence on digestion and the body’s utilization of food. It also entails the risks associated with major surgical procedures. Surgery therefore should never be the first option considered, but should only be chosen after all other options have failed or offer no hope of success. The procedures are not routinely covered by health insurance, each intervention must be individually applied for and justified. In addition to medical criteria for when an operation is indicated, further requirements must be met before health insurance will assume the costs for such an operation. The criteria are as follows:

- The patient is between 18 and 65 years old.

- Has a BMI >40 kg/m² or a BMI >35 kg/m² and is suffering from obesity-related health problems, e.g. diabetes, joint problems, heart problems, and sleep apnea.

- The patient has been overweight for more than 5 years.

- Multimodality conservative therapy was tried for more than 6 months without success.

- The patient has no other disease that could account for the weight problem.

- Sufficient compliance is expected

- The patient does not abuse alcohol or drugs

An adequate attempt at conservative treatment must be based on the three elements movement, diet, and behavior. These elements must be applied simultaneously and in coordination with one another. Supplemental medications can also be given. Any attempt at conservative therapy that does not include the above three elements will be turned down as inadequate by health insurance companies.

Surgical Procedures

Procedures for weight loss surgery, also known as bariatric surgery, are based on the two principles restriction and malabsorption, or a combination of the two.

Restrictive Procedures

The goal of restrictive procedures is to reduce the amount of food that can be consumed at a single sitting. The feeling of satiety should start sooner and last longer. The classical example of such a procedure is the Swedish adjustable gastric band (SAGB).

Gastric Band

In a minimally invasive laparoscopic procedure, the SAGB is placed on the upper portion of the stomach. The band can be tightened by filling a port chamber with fluid from outside. Ingestion of portion sizes that are too large can lead to vomiting or dilation of the esophagus. If this happens too often, the SAGB can lose it effectiveness.

The SAGB is a foreign body that is normally well tolerated by the body. In principle, therefore, it can remain in the body for a lifetime, even after the desired weight has been reached. If the band is removed, patients usually gain weight again.

In restrictive procedures like SAGB, the success of therapy depends on the collaboration and cooperation of the patient.

Sleeve Gastrectomy

In sleeve gastrectomy, or gastrectomy using the left-lateral approach, a large portion of the stomach is surgically removed, leaving a long gastric sleeve that holds much less food than previously.

The manner of function is mainly restrictive, like the gastric band. The gastric sleeve procedure, however, resects the portion of the stomach that synthesizes hormones that regulate appetite, feelings of hunger and satiety, among them ghrelin. Thus it not only restricts the volume of food intake, but it also alters the sensations of hunger and satiety – also taste – thus establishing a reliable and long-lasting loss of weight.

Malabsorptive Procedures

In malabsorptive procedures, the physiology of digestion is changed so that only a portion of the ingested food is absorbed by the body, thus reducing the intake of calories. This benefit, however, comes at the price of potential symptoms of severe vitamin deficiency, fatty stools, and extreme flatulence. These drawbacks make malabsorptive procedures, one of whose classic representatives is biliopancreatic diversion (BPD), an exceptional indication.

Gastric Bypass

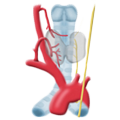

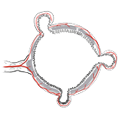

The classic example of combined restrictive and malabsorptive weight loss surgery is gastric bypass. In this procedure a small portion of the stomach, called a pouch, is surgically separated from the remainder of the stomach and remains in the body. A portion of the small intestine is anastomosed to this pouch (Vormagen), bypassing the duodenum and proximal portion of the jejunum, and separating the alimentary limb from the biliopancreatic limb

The digestive enzymes do not meet the food bolus until late in the Y-Roux jejuno-jejunostomy. Only beyond this point does normal digestion occur. Because the alimentary limb, i.e. the portion through which the chyme passes without encountering digestive enzymes, is ca. 150 cm long, it was once assumed that a certain malabsorption would occur. This is disputed now, at least when the alimentary limb is this long.

OP-Video: Y-Roux Gastric Bypass

1 Placement

- The patient is placed in the lithotomy position. At the start of surgery, the patient is brought into an almost sitting position, which facilitates performance of the procedure in the upper abdomen.

- In some cases, medications may be given to support the patient’s circulation.

2 Trocar positioning & Liver Traction

- Access is gained under video control with a blunt dissection trocar 21 cm below the xiphoid process

- The individual layers of the abdominal wall can be penetrated under visual control

- CO2 is insufflated to establish a capnoperitoneum

- The surgeon stands between the patient’s legs

- Two further trocars are placed after exploratory puncture with a long needle to prevent incorrect placement of the trocars, which would complicate the procedure

- Because the left hepatic lobe would normally be in the way during the procedure, it is held up and out of the way using a liver retractor (a number of retraction systems are available)

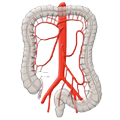

3 Division of the greater omentum

- The first step of the OP is the division of the greater omentum

- This is done because the small intestine will later be pulled up in front of the colon (antecolic) to the stomach

- To avoid tension on the anastomosis, the greater omentum is divided up to the transverse colon

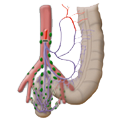

4 Identification of the ligament of Treitz

- After Dissection of the greater omentum, the transverse colon is lifted

- The ligament of Treitz is identified

- This step is crucial to identify the correct limb for the lower anastomosis

- The later biliopancreatic limb is measured up to 60 cm and is fixated with a suture to the remnant stomach.

5 End-to-side lower anastomosis

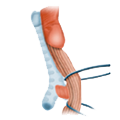

- Starting at the stay suture, the alimentary limb is measured to a length of ca. 150 cm and another stay suture placed. Chyme will later be transported through this limb absent bile and digestive enzymes

- An enterotomy incision is made in the alimentary limb and another in the biliopancreatic limb

- Nun wird in den alimentieren und den biliopankreatischen Schenkel je eine Enterotomie angelegt

- An end-to-side (Fußpunkt) anastomosis is created with a 60 mm stapler. The enterotomy is closed with a running suture

- To prevent a later internal hernia, the mesenteric incision is closed with titanium staples

6 Dissection of the gastric pouch

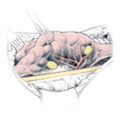

- The surgeon now creates the gastric pouch from the stomach

- This should not be larger than 30 ml Dissection is begun at the angle of His between the cardia and gastric fundus at the later withrawal site of the linear stapler

- The surgeon next dissects the lesser curvature in the bursa omentalis to allow introduction of the stapler behind and in front of the stomach

- Before firing the stapler, it must be confirmed that the stomach probe has been completely removed

- After placing a horizontal staple, vertical staples are placed up to the prepared angle of His

- The gastric pouch is completely detached from the remainder of the stomach

7 Inserting the Stapler Head

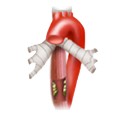

- The gastrojejunostomy is performed with a 25 mm circular stapler, which consists of two parts, the device itself, and the stapler head

- It is inserted through the mouth with a stomach probe

8 Gastrojejunostomy

- To perform the esophagogastrostomy the small intestine must be opened

- The stapler is inserted at this site, the central anvil of the stapler is pushed out and joined with the stapler head in the stomach

- The anastomosis is now fired and the stapler completely withdrawn

9 Small Intestine Resection

- The segment of the small intestine used for introduction of the circular stapler would constitute a functional shunt between the upper and lower anastomosis

- It is therefore freely mobilized and resected with the linear stapler

- To prevent contamination of the abdominal wall, the resected portion is removed from the abdomen in a specimen pouch

10 Closure of the Trocar Incision

- For insertion of the circular stapler, the lower left access is dilated to 26 mm

- To prevent an abdominal wall hernia in this area the abdominal wall is sutured

11 Methylene blue water tightness test & Conclusion

- To test the watertightness of the anastomosis, the pouch is filled with methylene blue solution. The pouch is filled to capacity at 30 ml

- To prevent twisting of the gastrojejunostomy, the efferent alimentary limb is affixed to the residual stomach with resorbable suture

- SA Robinson drain is placed at the upper anastomosis

- To conclude, the liver retractor and the trocars are removed under visualization, the pneumoperitoneum is released and the wounds closed

OP-Schemazeichnung

After Surgery

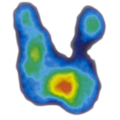

After gastric bypass surgery patients initially feel no or clearly less hunger, their senses of taste and smell are changed, and they experience very rapid loss of weight. The weight loss is not solely explained by restriction or malabsorption. Surprisingly, after gastric bypass surgery despite the dramatically reduced calorie intake the body’s total energy consumption increases. In contrast, the reduced energy intake leads automatically to a drop in the basal metabolic rate, which hinders further weight loss or, if the low calorie diet ever ends, leads to rapid renewed weight gain.

A further dramatic effect concerns diabetes mellitus. Presumably the duodenal exclusion and the early contact of food with the distal jejunum result in a series of humoral changes that disrupt the extreme insulin resistance. Many patients who required high insulin dosages prior to surgery are able to dramatically reduce the dosage or completely stop after surgery.

This effect is so great that it is currently discussed whether to operate on normal weight or slightly obese diabetic patients whose diabetes can no longer be controlled by conventional means. This metabolic surgery will probably become even more widely adopted in future, even if the mechanisms underlying the effects are still not entirely understood.

All bariatric surgery can now be carried out minimally invasively at acceptable risk. The prerequisite is an interdisciplinary center in which all participating specialties are represented, including conservative therapy, assessment of indications for surgery, preparation and performance of the surgery itself and, most importantly, the lifelong follow-up care of patients. To prevent deficiency symptoms after gastric bypass, patients must take vitamin and mineral supplements for the rest of their lives, since these are absorbed in the proximal gastrointestinal tract. The recognition and treatment of other complications also requires a high degree of experience and expertise.

In 2009, therefore, the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery developed guidelines for certifying clinics as obesity centers. To qualify, centers must meet certain infrastructural requirements, have a surgical team experienced in treating obesity, and have performed a minimal number of bariatric interventions.

At the Centre for Obesity Medicine in Wuerzburg, morbidly obese patients have been treated surgically since 1997.

Wound Healing

Wound Healing Infection

Infection Acute Abdomen

Acute Abdomen Abdominal trauma

Abdominal trauma Ileus

Ileus Hernia

Hernia Benign Struma

Benign Struma Thyroid Carcinoma

Thyroid Carcinoma Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism Hyperthyreosis

Hyperthyreosis Adrenal Gland Tumors

Adrenal Gland Tumors Achalasia

Achalasia Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal Carcinoma Esophageal Diverticulum

Esophageal Diverticulum Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal Perforation Corrosive Esophagitis

Corrosive Esophagitis Gastric Carcinoma

Gastric Carcinoma Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic Ulcer Disease GERD

GERD Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric Surgery CIBD

CIBD Divertikulitis

Divertikulitis Colon Carcinoma

Colon Carcinoma Proktology

Proktology Rectal Carcinoma

Rectal Carcinoma Anatomy

Anatomy Ikterus

Ikterus Cholezystolithiais

Cholezystolithiais Benign Liver Lesions

Benign Liver Lesions Malignant Liver Leasions

Malignant Liver Leasions Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis Pancreatic carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma