Definition

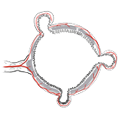

A diverticulum is an outpouching of a hollow organ. There are both true and false diverticula. An example of a true diverticulum in the gastrointestinal tract is Meckel’s diverticulum, where the entire wall of the small intestine outpouches as a remnant of the omphalomesenteric duct.

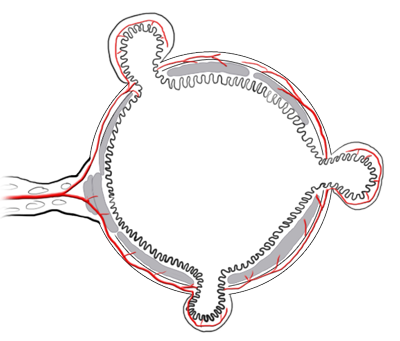

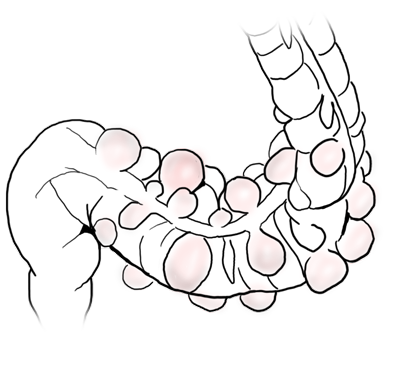

If only a part of the bowel wall is affected, one speaks of a false diverticulum. Colon- and sigmoid diverticula are false diverticula’s where the mucosa of the bowel protrudes outward through preexisting gaps in the muscle.

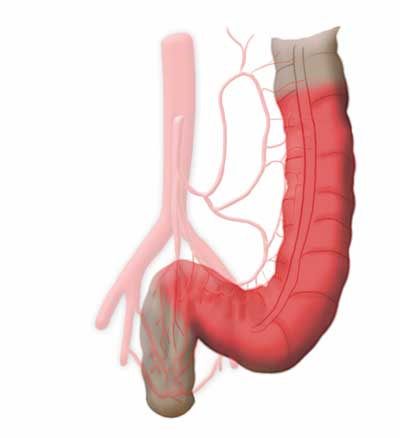

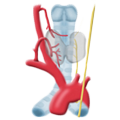

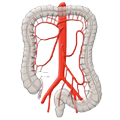

The weak points at which this happens are the entry sites of the intestinal vascular supply, which runs through the mesentery (a double fold of the peritoneum through which the vessels of the visceral organs run). The vessels run along the exterior of the bowel then enter the bowel radially through the muscularis to supply the mucosa with blood.

Etiology

The presence of a sigmoid diverticulum is not pathological in itself since diverticula generally remain asymptomatic. Many, chiefly older people have multiple diverticula without ever experiencing complaints. As a rule of thumb it can be said that about 70% of people over age 70 have diverticula.

The cause of diverticula in the Western world can be sought in our dietary habits. A diet that routinely contains too little fiber creates low stool volume, thus increasing wall tension in the colon, mainly in the distal segments. Diverticula almost never occur in the rectum, because its wall structure and muscle layers differ from those of the rest of the colon.

Here there is no antegrade peristalsis, the rectum has rather a collection and reservoir function. This is evident macroscopically since the rectum has no tenia coli.

Stools can become lodged in diverticula, leading to diverticulitis, an inflammation of the bowel wall. This usually follows an intermittent course, the first episode being statistically the most dangerous because the risk of perforation is greatest. Such an inflammation can lead not only to perforation of the bowel but also a phlegmon of the bowel wall. A perforation that is covered by the bowel wall or mesentery is called a concealed perforation, but a free perforation in the abdominal cavity is also possible.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

Typically patients describe localized pain in the left lower abdomen. On clinical examination, patients exhibit marked abdominal tenderness here. It is important on first examination to determine whether local abdominal guarding or generalized peritonism is present.

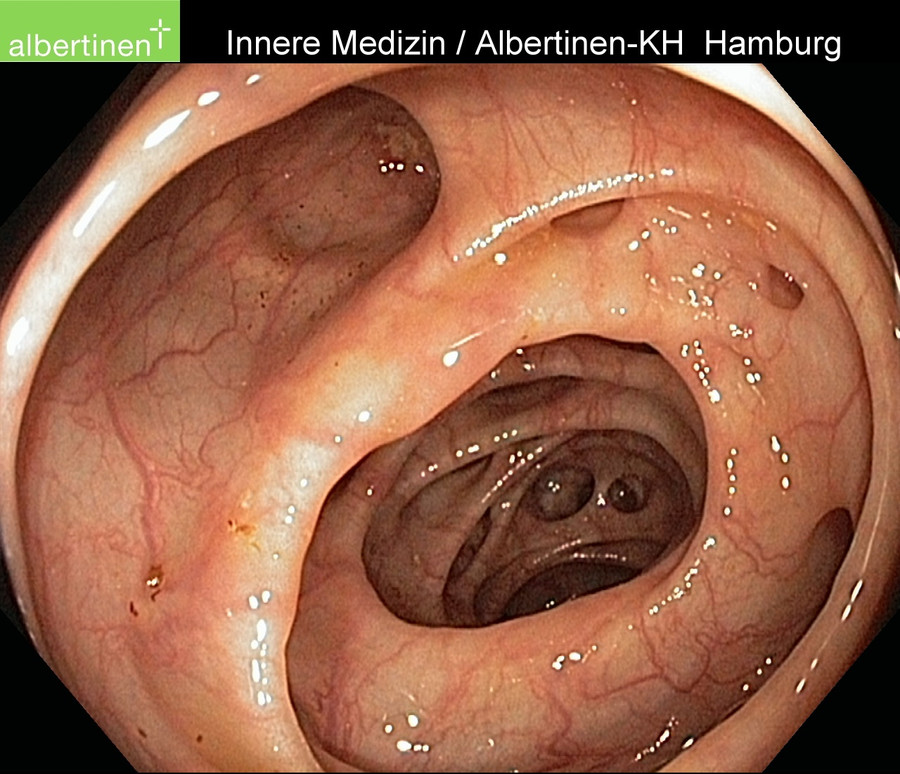

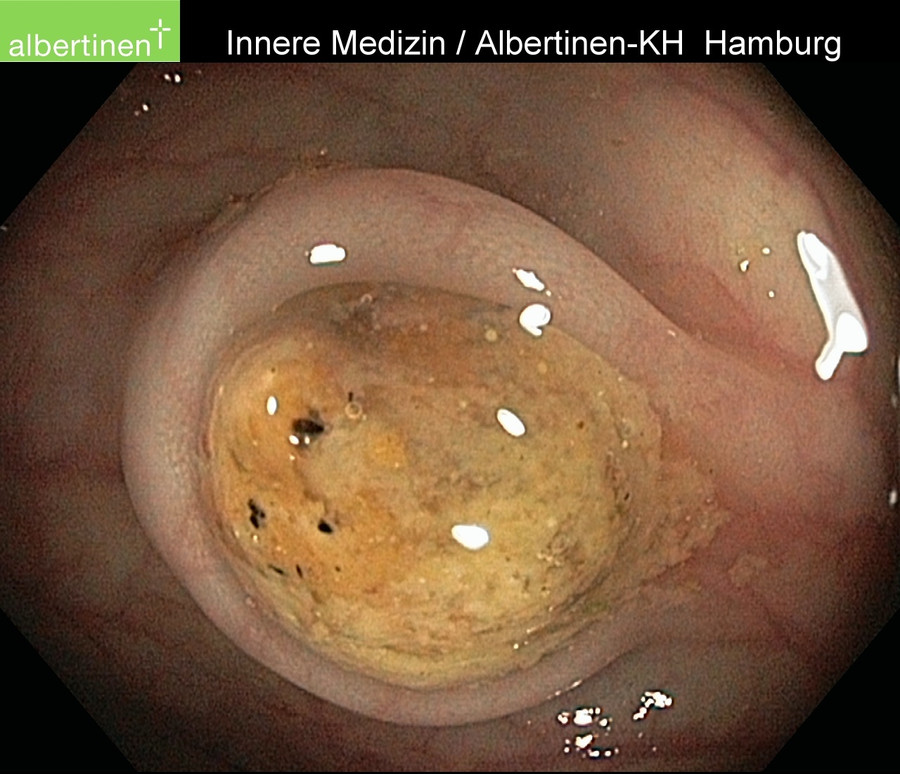

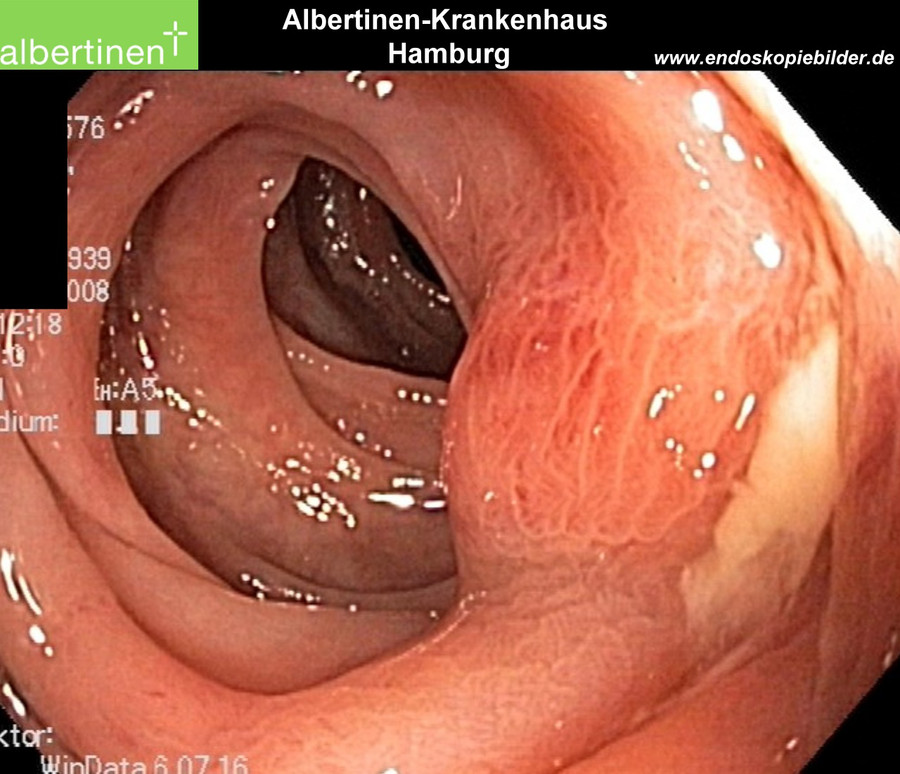

The finding of a diverticulitis is often known from a prior colonoscopy, which can provide a further anamnestic clue, as can prior episodes of diverticulitis. In the acute phase of diverticulitis, colonoscopy is contraindicated due to the clearly elevated risk of perforation. Moreover, diverticulitis is not diagnosed by colonoscopy, since the disease process occurs mainly outside the bowel and thus eludes endoluminal diagnosis. Before elective surgery for sigmoid diverticulitis, however, colonoscopy always be done to exclude a colon carcinoma. If colon carcinoma is found, oncological radical resection is indicated, not tubular resection of the sigmoid as for benign sigmoid diverticulitis.

The surgical strategy for diverticulitis is completely different from that for oncological bowel resection. A carcinoma always involves radical resection with systematic lymphadenectomy, i.e. radicular resection. For diverticulitis by contrast tubular resection, i.e. close to the bowel, is performed only on the immediate inflamed area of the large intestine. Care should always be taken, however, that distally no part of the sigmoid colon is left since otherwise there is a risk of recurrence.

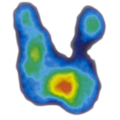

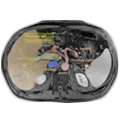

In emergency situations, it should first be determined whether there is an indication for emergency surgery, such as a free perforation. This can be done by x-ray of the abdomen in a standing or left lateral position. The presence of large volumes of free abdominal air points to perforation and would require immediate surgery. Ultrasound can detect bowel wall thickening and free abdominal

fluid. If there is no radiomorphological or clinical suspicion of a free perforation, then treatment can begin with antibiotics and the patient placed on a restricted diet. This usually leads to a rapid improvement in symptoms.

For further diagnosis, computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen using a rectal contrast agent can help to reliably assess the disease’s severity. Once colon contrast enemas were used, but they are now obsolete for diagnosing the severity of acute diverticulitis since they can show only diverticula within the bowel but not the extraluminal peridiverticulitis. Because the severity of acute diverticulitis depends on the extraluminal inflammatory reaction, i.e. the peridiverticulitis, colon contrast enema here is ineffective as a diagnostic method because the extraluminal portion of the inflammation cannot be shown.

Endoscopic findings

Classifications

Numerous classifications have been developed for diverticulitis. Because clinicians need a classification that does not depend on intraoperative findings or a pathologist’s report, the classification of Hansen & Stock has become the standard for clinical practice.

The current guidelines for treatment of diverticula disease use a different classification, the Classification of Diverticular Disease.

Hansen & Stock classification

| Type 0 | Asymptomatic diverticulosis | |

| Incidental finding; asymptomatic No disease |

||

| Type 1 | Uncomplicated sigmoid diverticulitis | |

| Type 2 | Acute complicated diverticulitis | |

| Type 2a | Phlegmonous sigmoid diverticulitis | Peridiverticulitis without perforation |

| Type 2a | Covered perforated sigmoid diverticulitis | Paracolic air in CT without free perforation |

| Type 2c | Free perforated sigmoid | Free perforation, free air / fluid, generalized peritonitis |

| Type 3 | Chronic recurrent sigmoid diverticulitis

Recurrent or persistent symptomatic diverticular disease |

You can find the current S2k-Guidlines on diverticulitis here: www.awmf.de

Classification of diverticular disease - CDD

| Type 0 | Asymptomatic diverticulosis | |

| Incidental finding; asymptomatic No disease |

||

| Type 1 | Acute uncomplicated diverticular disease / diverticulitis | |

| Type 1a | Diverticulitis / Diverticular disease without peridiverticulitis | Signs of inflammation (laboratory tests): mandatory; cross-sectional imaging: phlegmonous diverticulitis |

| Type 1b | Diverticulitis with phlegmonous peridiverticulitis | Signs of inflammation (laboratory tests): mandatory; cross-sectional imaging: phlegmonous diverticulitis |

| Type 2 |

Acute complicated diverticulitis like 1b, additional: |

|

| Type 2a | Microabscess | Concealed perforation, small abscess (≤1 cm); minimal paracolic air |

| Type 2b | Macroabscess | Paracolic or mesocolic abscess (>1cm) |

| Type 2c | Free perforation | Free perforation, free air / fluid generalized peritonitis |

| Type 2c1 | Purulent peritonitis | |

| Type 2c2 | Fecal peritonitis | |

| Type 3 | Chronic diverticular disease

Relapsing or persistent symptomatic diverticular disease |

|

| Type 3a | Symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) | Localized symptoms; laboratory test (calprotectin): optional |

| Type 3b | Relapsing diverticulitis without complications | Identification of stenoses, fistulas, conglomerate tumor |

| Type 3c | Relapsing diverticulitis with complications | Identification of stenoses, fistulas, conglomerate tumor |

| Type 4 | Diverticular bleeding | Diverticula identified as the source of bleeding |

Complications

Diverticulitis can give rise to a series of complications. In addition to perforation with consequent peritonitis, it can cause abscesses or fistulas into neighboring organs or the skin. Chronic recurring inflammation can lead to thickening of the bowel wall and thus to stenosis. Diverticular bleeding can also result. The latter is often difficult to locate, which can frustrate attempts at endoscopic hemostasis.

Indication for surgery

The question which patient should undergo surgery when and for what reason requires careful deliberation for diverticulitis. If there is a free perforation, emergency laparotomy is of course indicated. For patients with four-quadrant fecal peritonitis, a temporary ileostomy may be necessary to prevent a return of peritonitis in the event of anastomotic insufficiency.

If the patient becomes unstable due to e.g. an incipient or manifest sepsis, the operation may need to be ended as soon as possible. If this happens, a Hartmann’s discontinuity resection may be performed, where the end of the descending colon is brought out for terminal colostomy and the rectum ends blindly inside the body.

There is no risk of anastomotic insufficiency, but the rectal stump may become insufficient. Reconnection surgery after Hartmann’s procedure, however, is incomparably more complicated and risky for the patient than reversal of a double-barreled ileostomy. Whenever possible, therefore, a continuity resection should be performed with placement of an anastomosis and if needed the anastomosis diverted with an ileostomy.

If no free perforation is present, enough time is available to treat the patient with antibiotics and to lift him or her out of the acute stage of the diverticulitis. Elective surgery after the acute inflammatory reaction has subsided is associated with much lower morbidity and lethality. Moreover, during the complaint-free interval there is enough time to perform a colonoscopy to rule out a colon carcinoma, since colon carcinoma with perforation causes symptoms similar to those of a perforated diverticulitis. Moreover, CT is also not able to clearly distinguish the two types of perforation. A concealed perforation is therefore an absolute indication for elective surgery.

Phlegmonous diverticulitis is a relative indication for surgery. It was once thought that every episode of the disease increased the risk of perforation, but this now know to be false.

An uncomplicated diverticulitis in Hansen & Stock stage I is treated conservatively, usually by a family physician on an outpatient basis. An exception is high risk patients undergoing immunosuppression or who have received a transplant. In these patients with Hansen & Stock grade I diverticulitis the indication for elective surgery should be made generously, because the risk of perforation is higher and the resulting complications more serious.

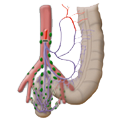

Surgical Principles

The basic principle is tubular resection of the inflamed bowel segment, ensuring that the resection extends into the rectum since otherwise there is a risk of recurrence. In contrast to oncological resection, the inferior mesenteric artery is not resected close to the aorta but close to the bowel, thus preserving the blood supply to the descending colon.

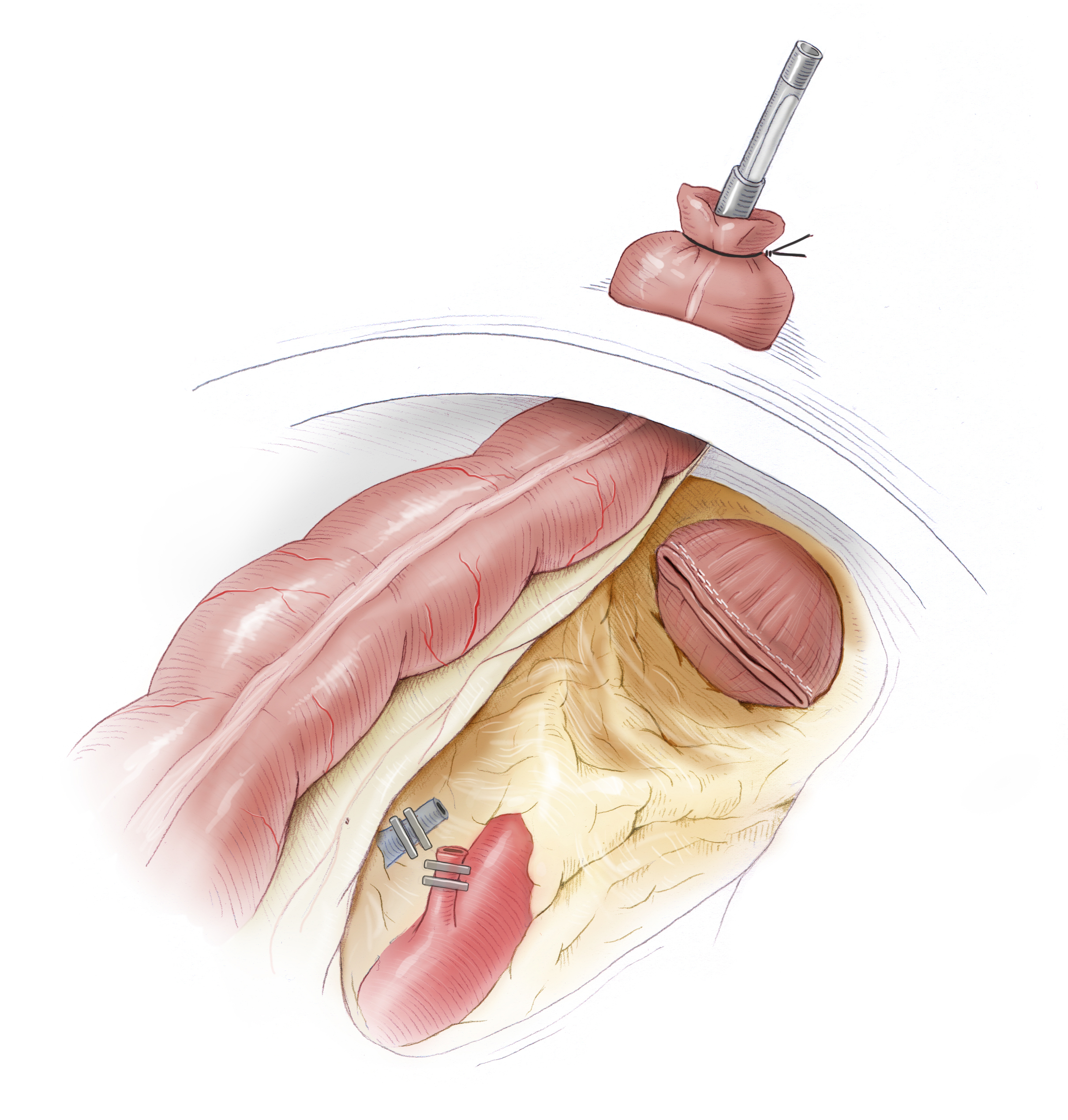

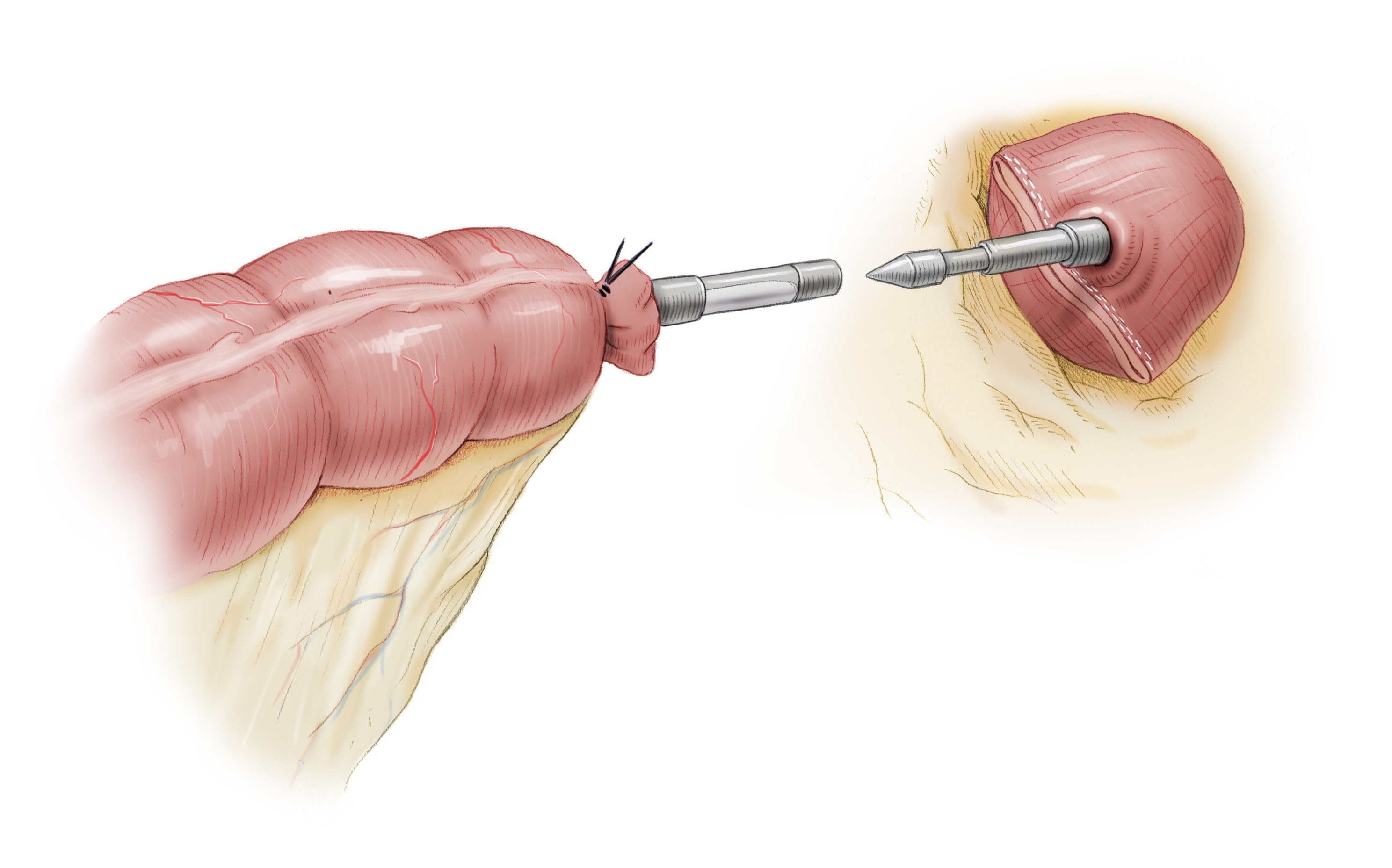

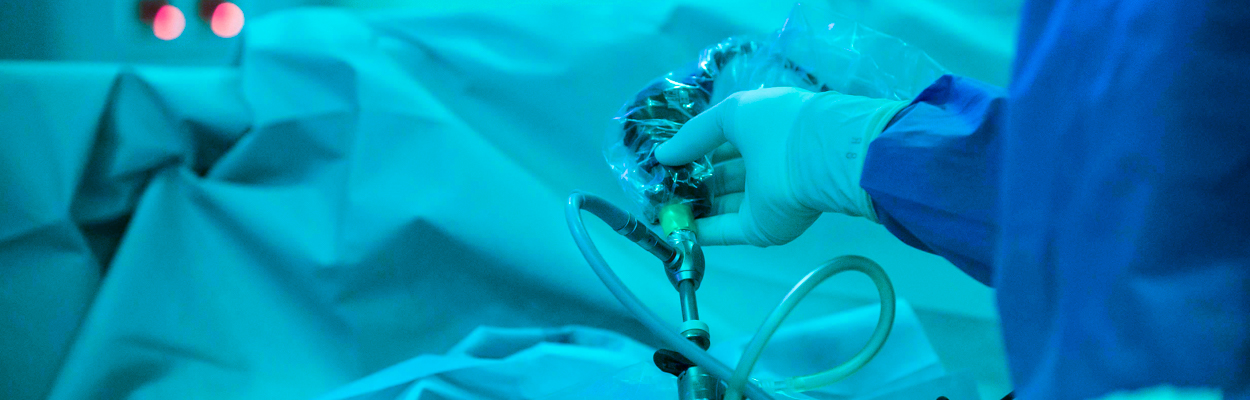

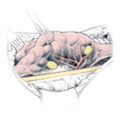

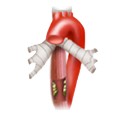

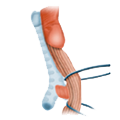

For elective surgery, dissection of the sigmoid colon and descending colon as well as mobilization of the left colic flexure can usually be done laparoscopically. Through a Pfannenstiel incision the specimen can be removed and the anastomosis prepared with a circular stapler. The stapler consists of two parts, the upper part, the anvil is sewn to the descending colon with sutures. This step is performed extracorporeally. The bowel is then returned to the body and the abdomen closed. The procedure continues laparoscopically. From transanal, the -second part of the stapler is introduced and its anvil (Dorn) is used to push through the blind rectum left after resection of the bowel. Both parts of the stapler are joined together and the stapler fired. It automatically completes several rows of staples and severs the bowel with a circular scalpel. Thus the bowel continuity is restored. The advantages of laparoscopic surgery lie -- along with its superior cosmetics -- in the speedier patient recovery and the lower risk of incisional hernia.

Laparoscopy-assisted Sigmoid Resection

After laparoscopic mobilization of the colon and the left colic flexure, the specimen is removed through a Pfannenstiel incision and the anastomosis prepared. This is done by affixing the stapler head of the circular stapler in the descending colon with a tobacco pouch suture. The bowel is then repositioned again intraabdominally with the stapler head, the minilaparotomy closed, and the procedure continued laparoscopically.

To complete the termino-terminal descendorectostomy, a circular stapler is introduced transanally, the blind rectal stump is stapled with the stapler’s central anvil. The stapler is then joined with the stapler head in the descending colon and the anastomosis completed with the stapler.

Wound Healing

Wound Healing Infection

Infection Acute Abdomen

Acute Abdomen Abdominal trauma

Abdominal trauma Ileus

Ileus Hernia

Hernia Benign Struma

Benign Struma Thyroid Carcinoma

Thyroid Carcinoma Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism Hyperthyreosis

Hyperthyreosis Adrenal Gland Tumors

Adrenal Gland Tumors Achalasia

Achalasia Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal Carcinoma Esophageal Diverticulum

Esophageal Diverticulum Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal Perforation Corrosive Esophagitis

Corrosive Esophagitis Gastric Carcinoma

Gastric Carcinoma Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic Ulcer Disease GERD

GERD Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric Surgery CIBD

CIBD Divertikulitis

Divertikulitis Colon Carcinoma

Colon Carcinoma Proktology

Proktology Rectal Carcinoma

Rectal Carcinoma Anatomy

Anatomy Ikterus

Ikterus Cholezystolithiais

Cholezystolithiais Benign Liver Lesions

Benign Liver Lesions Malignant Liver Leasions

Malignant Liver Leasions Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis Pancreatic carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma