Anatomy

The middle rectal artery is present in only ca. 20% of cases.

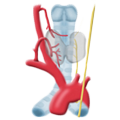

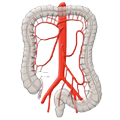

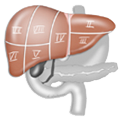

The rectum lies within the pelvis in close proximity to the seminal vesicles and prostate in males and to the vagina and uterus in females. The lower two thirds are located outside the peritoneum where it is surrounded by perirectal fat, the mesorectum, through which the vessels supplying the rectum and the lymphatic pathways run. The blood supply to the rectum is divided, a feature that goes back to embryonal development. The upper portion of the rectum is supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery via the superior rectal artery. The middle and lower portions are supplied by the flow area of the internal iliac artery. The middle rectal artery is present in only ca. 20% of cases. The lower portion of the rectum is supplied by the inferior rectal artery, which has its origin in the internal pudendal artery, a branch of the internal iliac artery.

arterial blood supply/h3>

left colic artery sigmoid artery superior rectal artery

medial rectal artery lower rectal artery

venous drainage

venous drainage portal vein lower hollow vein

lymphnodes

Venous Drainage

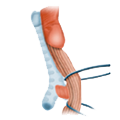

The venous drainage is also divided, the portal venous drainage crossing the caval venous drainage area at the rectum, thus creating in effect a portocaval anastomosis. The lower two thirds drain directly into the vena cava, the upper portion flows through the inferior mesenteric vein into the portocaval circulation. The lymphatic pathways and lymph nodes run along the arterial vessels. The extent of the lymphadenectomy determines the extent of the bowel resection. To ensure that all lymph nodes of the drainage area are removed, the inferior mesenteric artery must be ligated (unterbunden) near its origin at the aorta. It is disputed whether this „high tie" technique has advantages for overall survival or risk of recurrence over the „low tie“, i.e. resection at the level of the sigmoid artery while leaving the left colic artery.1,2

Introduction

Rectal carcinoma differs in essential points from colon carcinoma. This is true of their symptoms and clinical picture as well as of the diagnostic and therapeutic strategies used to treat them. Two thirds of all colorectal carcinomas are located in the rectum. About one half of them can be diagnosed by a ubiquitous, always available, and quick diagnostic method that is as reliable as it is inexpensive: the finger.

A digital-rectal exam can deliver a wealth of information regarding a palpable mass in the rectum. A finding can be made up to 8-10 cm superior to the anocutaneous line. In addition to the size of the mass within the lumen (e.g. semicircular sub-stenosing mass), the experienced examiner can estimate its mobility relative to the rectal wall. The more mobile the mass, the shallower its invasion depth. This so-called Mason-classification correlates surprisingly well with the patient’s overall prognosis of the patient.

Of particular importance in rectal carcinoma is the diagnosis of tumor spread, called staging. Patients with locally advanced carcinomas benefit from neoadjuvant therapy prior to radical surgery and lymphadenectomy. The good results of neoadjuvant therapy cannot be achieved by follow-up treatment alone, it is therefore essential for the patient that the tumor is staged as precisely as possible prior to surgery.3,4

Symptoms

Blood in the stool is always suspicious for carcinoma!

The problem rectal carcinomas pose for diagnosis is that they remain asymptomatic so long. All of their symptoms are late symptoms and signs of advanced tumor growth. Blood in the stool is always suspicious and should be conclusively clarified, with colonoscopy if necessary. The simple tentative diagnosis „bleeding hemorrhoids“ should never be left to stand without further clarification.

Changes in bowel habits can also be suspicious for rectal carcinoma, especially if stools are pencil thin or if constipation alternates with diarrhea, termed paradoxical diarrhea This may be caused by a stenosing tumor, which causes an obstruction. A fermentation process leads to liquefaction of the stool and can result in an explosive defecation. Every disturbance of continence requires diagnostic clarification. Patients who report so-called „oops poops,“ i.e. involuntary leakage of stool while passing gas, may be pointing to a deep seated rectal carcinoma that is interfering with fine continence.

The problem rectal carcinomas pose for diagnosis is that they remain asymptomatic so long. All of their symptoms are late symptoms and signs of advanced tumor growth. Blood in the stool is always suspicious and should be conclusively clarified, with colonoscopy if necessary. The simple tentative diagnosis „bleeding hemorrhoids“ should never be left to stand without further clarification.

Changes in bowel habits can also be suspicious for rectal carcinoma, especially if stools are pencil thin or if constipation alternates with diarrhea, termed paradoxical diarrhea This may be caused by a stenosing tumor, which causes an obstruction. A fermentation process leads to liquefaction of the stool and can result in an explosive defecation. Every disturbance of continence requires diagnostic clarification. Patients who report so-called „oops poops,“ i.e. involuntary leakage of stool while passing gas, may be pointing to a deep seated rectal carcinoma that is interfering with fine continence.

Diagnosis

Rectal carcinoma therapy depends on precise determination of the pretreatment stage of the tumor.

Digital Rectal Exam

The first step in determining tumor stage is the digital rectal exam, which can aid in clinical staging based on tumor mobility applying the aforementioned Mason classification, and also reveal the distance of the tumor from the sphincter system and aid in the assessment of sphincter tone.

Colonoscopy

A complete colonoscopy belongs to the standard repertoire for diagnosis of rectal carcinoma. Screening colonoscopy often produces incidental findings that are then confirmed histologically. Colonoscopy can discover a concurrent colon carcinoma, termed a synchronous second carcinoma. This is especially common in hereditary forms of colorectal carcinoma. If colonoscopy fails, e.g. due to a stenosing tumor growth, then colonoscopy must be performed postoperatively. Even after successful colorectal carcinoma surgery, a colonoscopy should be performed every 3 years to exclude a time-delayed carcinoma in the large intestine (metachronous colorectal cancer).

Localization

It is important to know the location of a colorectal carcinoma for both patient and surgeon. The distance of a tumor from the sphincter apparatus determines whether it can be operated on while preserving continence and thus has a decisive influence on surgical strategy. Because rectal carcinomas usually grow directly through the wall of the rectum and do not spread very far longitudinally, a safe resection margin of ca. 2 cm is generally sufficient. A distance from the pectinate line of more than 2 cm is ideal for continence-preserving surgery. Assessment of this distance by endoscopy is inexact as bending of the colonoscope can easily lead to a mismeasurement of 10 cm to 20 cm or even more in the oral portion of the colon. Reliable diagnosis of location is therefore not possible with colonoscopy.

Rectoscopy

should therefore always be done with an inflexible instrument, i.e. with a rectoscope. This can precisely measure both the upper and lower margins of the tumor, i.e. its longitudinal extension, and its distance from the pectinate line as a landmark for the sphincter muscle level. If not already done during endoscopy, a biopsy should be taken during rectoscopy. The rectal mucosa is not sensitive to pain, therefore during the biopsy the patient feels only a dull pricking sensation. The anoderm, by contrast, is very well innervated and thus very sensitive to pain. A biopsy should only be taken from this area under adequate analgesia.

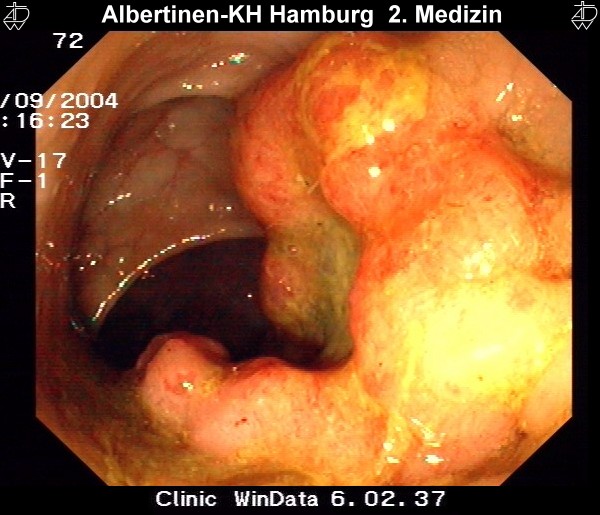

by courtesy of Albertinen-Krankenhaus Hamburg

Colonoscopy & Polypectomy

Endoscopic polypectomy in a patient with a very large polyp in the rectum. Because the polyp has a very long stalk, it can be completely removed with a cautery snare, as later confirmed by histology.

After resection, the polyp is caught with the snare and extracted through the anus.

Endosonography & Magnetic Resonance Tomography (MRT)

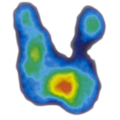

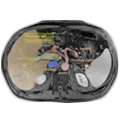

Endosonography and MRT of the pelvis are equally suited for assessing the depth of rectal wall infiltration and the extent of locoregional lymph node invasion. Ultrasound is rightly considered to be examiner dependent. Experienced diagnosticians attain a precision of 90% for infiltration depth, 70% for lymph node staging. MRT is also not entirely examiner independent, reliable results depend to a large extent on device settings and the coils used.

One respect MRT in which is superior to endosonography is the depiction of the pelvirectal fascia. The distance from the tumor to the visceral pelvic fascia is important prognostically and could in future influence the decision for or against neoadjuvant therapy. Patients with a circumferential margin of less than 1 mm or whose pelvirectal fascia has been penetrated (durchbrochen) have an elevated risk of recurrence even after optimal surgery. 5

Endosonography Example

This patient has a locally advanced, stage uT3 uN+ rectal carcinoma. Endosonography shows the normal 5-layers of the rectum comprised of the wall layers and sonographic boundaries. A bulging mass beneath the wall layers is evident at 5-6 o’clock lithotomy position. Readily visible is how the tumor penetrates the outer echo-poor layer representing the serosa. The patient received long-term neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy over 6 weeks and the tumor was later resected in a curative (R0) procedure that preserved continence .

Endosonography

Endosonography allows excellent assessment of a tumor’s spread along the rectal wall layers. Usually 5 layers are visible in ultrasound of the rectum correspond to its wall layers and including the sonographic boundaries. Enlarged lymph nodes can also be easily recognized without, however, revealing whether they are benign or malignant. Inflamed lymph nodes may also be enlarged, especially a few days after biopsy. Still, every enlarged lymph node is suspicious for metastasis and is assigned the grade uN+. Tumor uT3 lymphnodes uN+Classification

Rectal carcinomas were originally classified according to the DUKES staging system, which was introduced in 1932. In Europe this classification has lost its clinical relevance. The current classification is the UICC classification, which is based on the TNM classification.

TNM 7 2009 – deutsche Auflage 2010

CT of the Thorax & Abdomen

The question of distant metastases is best answered by CT of the thorax and abdomen. The main lymphatic drainage runs along the portocaval venous system via the inferior mesenteric vein. The lower portion of the rectal venous plexus, however, drains directly into the vena cava, thus bypassing the flow area of the liver and avoiding the „first pass effect“ of the liver. This explains not only why medications applied rectally are uptaken more rapidly, but also why rectal carcinoma metastases first appear in the lungs. According to current guidelines, ultrasound of the abdomen and x-ray are sufficient for staging of a rectal carcinoma, but because CT is now almost universally available and cost-effective and the possible radiation injury in comparison to overlooked metastases to be regarded as inferior.

Tumor Markers

The decrease in the tumor marker carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) prior to surgery establishes a baseline value. If this value falls after R0 resection, a renewed increased points to a recurrence or metastasis. CEA is unsuited as a screening parameter.

Staging

Precise staging is the basis for treatment based on established guidelines. The goal of rectal carcinoma surgery is the radical removal of the tumor while maintaining an adequate safe resection margin. For well-differentiated tumors 2 cm are sufficient, poorly differentiated tumors need a larger margin.

Another important oncological principle is the complete resection of locoregional lymph nodes. Because the lymph nodes travel along the arteries, this is achieved by resection of the inferior mesenteric artery. It is disputed whether ligation at its aortic origin (“high tie”) has an advantage over ligation at a point just below the origin of the left colic artery (“low tie”)

.1,2

The extent of bowel resection is determined by the circulatory situation after the lymphadenectomy

With „high tie“ ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery, a resection margin on the colon near the left flexure must be chosen because the bowel lying below this point becomes ischemic due to the ligation of the left colic artery. The blood supply after radical lymphadenectomy, therefore, determines the extent of bowel resection, which indeed far exceeds that necessary for a safe resection margin of 2 cm.

"high-tie" - Absetzen auf Höhe der A. mesenterica inferior

"low-tie" - Absetzen auf Höhe der A. sigmoidea

Neoadjuvant Therapy

Tumor location plays a major role in the choice of surgical strategy. Tumors in the upper third of the rectum are treated like colon carcinomas, i.e. no neoadjuvant therapy but primary resection of the carcinoma. An obligatory part of this strategy is partial mesorectal excision, or PME. Advanced tumors located in the middle and lower thirds of the rectum receive neoadjuvant therapy. The criteria for this is a T stage >=3 and/or V.a. lymph node metastasis. A carcinoma staged uT3 uN0 prior to therapy would therefore receive neoadjuvant therapy, just as would a tumor staged uT2 uN+. The prefix „u“ stands for ultrasound and is a common abbreviation for preoperative staging. Definitive staging is designated by a „p“ for pathology and supplemented with a „y“ for tumors receiving neoadjuvant therapy. A „ypT2 ypN0 (0/15) M0 G2 R0“ tumor is a tumor that has invaded the submucosa, undergone neoadjuvant therapy, and was completely removed without having any affected lymph nodes. In this patient, the pathologist found 15 lymph nodes, at least 12 lymph nodes should be examined to enable a definitive finding regarding a tumor’s N status. The goal of neoadjuvant therapy is to downsize the tumor and reduce the invasion depth, with consequent downstaging. This allows more tumors to be resected while preserving continence with simultaneous sparing of the important nerve plexus in the lesser pelvis. Neoadjuvant therapy does not affect overall survival, which is generally limited by the distant metastases. It does, however, increase the risk of local recurrence. Local recurrences of rectal carcinomas are difficult to treat and dramatically degrade patient quality of life due to local complications.

Long-Term versus Short-Term Radiochemotherapy

There are currently two main principles for neoadjuvant treatment of rectal carcinoma: short-term radiochemotherapy is administered for a week followed immediately by surgery, long-term radiochemotherapy is given for 6 weeks, beginning with radiation supplemented by chemotherapy with 5-Fluoruracil (5-FU). The 5-FU works as a radiosensitizer, making the tumor cells more sensitive to radiation. Long-term radiochemotherapy is followed by an interval of 6 weeks before surgery is performed. The morbidity of rectal resection is higher after neoadjuvant therapy, but the advantages for the patient still outweigh the disadvantages. Regarding the choice of neoadjuvant procedure the German S3 Guidelines for Colorectal Carcinoma state the following:

In situations in which a downsizing of the tumor is desirable (T4 tumors, insufficient safety margin to the mesorectal fascia in thin-layer MRI – margin of 1 mm or less – or desired sphincter preservation for tumors in the lower third), pre-operative radiochemotherapy should be preferred over short-term radiotherapy. For cT3 tumors or cN + tumors for which downsizing is not being attempted, pre-operative therapy can be conducted in form of either radiochemotherapy or short-term radiation.

Eine postoperative Radiochemotherapie bei initial unterschätztem Befund bringt schlechtere Ergebnisse bzgl. des Lokalrezidivs bei gleichzeitig deutlich erhöhter Komplikationsrate nach der Operation. 6

Postoperative radiochemotherapy for an initially understaged (unterschätztem) tumor increases the risk of local recurrence while raising the surgery-related complication rate.6 Neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy should be supplemented by adjuvant chemotherapy after radical surgery regardless of the postoperative tumor stage since it improves the overall and tumor-free survival of patients.7

Therapy in every patient with rectal carcinoma is determined by an interdisciplinary tumor board. Participants are gastroenterologists, oncologists, surgeons, radiotherapists, radiologists, pathologists and gynecologists.

Rectal Carcinoma Surgery

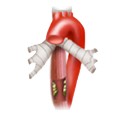

A distinction is made between anterior rectal resection of tumors of the upper third of the rectum, and deep anterior resection of tumors of the middle and lower thirds. Reconstruction is usually done by a stapled anastomosis. For this a circular stapler is often used which can simultaneously staple and cut and thus create the anastomosis between the bowel segments.

Unlike the colon, the rectum has no taenias and therefore no peristalsis. It serves rather as a reservoir for stool and provides sensory feedback felt as an urge to defecate. After resection this function is partially if not completely lost. To prevent propagation of the peristaltic wave of the descending colon directly to the rectum and sphincter apparatus, a pouch is created in most patients. This also serves to a certain extent as a reservoir. The current types are J pouch and coloplasty pouch.

The deeper the anastomosis is placed, the more marginal the perfusion, which increases the risk of postoperative anastomotic insufficiency with consequent pelvic phlegmon and sepsis. Therefore when deep anterior rectal resection is performed a protective ileostomy should always be placed. While this does not prevent the occurrence of an anastomosis insufficiency or change the perfusion status, the sequelae of an insufficiency are much less dramatic if the bowel has been diverted. Perhaps numerous small anastomotic insufficiencies remain clinically so inconspicuous that they are not diagnosed. Before an ileostomy is reversed, therefore, the presence of an anastomotic insufficiency or stenosis of the anastomosis must be ruled out.

For very deep carcinomas, abdominoperineal rectal resection may be necessary, which includes resection of the anus and channeling of the descending colon as a terminal descendostoma. Intersphincteric resection, i.e. abdominoperanal resection, is another possibility. This involves a hand suture anastomosis at the sphincter level, which requires ample surgical experience. Although its postoperative sphincter function and continence are initially poor, abdominoperineal resection with terminal colostomy is to be preferred, since with good stoma management it offers better quality of life and is more favorable for longterm care than continuous incontinence. Procedures for locally limited resection are also possible but have strict indication criteria. If the tumor is confirmed T1, which is no larger than 3 cm, and is well to moderately differentiated, a transanal full-thickness resection can be performed without radical lymphadenectomy. Of course no lymph nodes may be staged as suspicious, otherwise the procedure is contraindicated.

Complete resection must be confirmed histologically, otherwise a follow-up radical operation will be necessary. This method should not be used for T2 carcinomas since 10% to 20% of these tumors have already metastasized lymphatically.

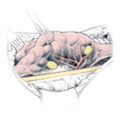

Total Mesorectal Excision (TME)

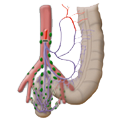

Two-thirds of the rectum lies outside the peritoneum, where it is surrounded by an oval-shaped body of adipose tissue containing the lymph nodes and vascular supply. This adipose tissue is wrapped in the pelvic fascia.

. Between these two fascia, the pelvic visceral fascia and parietal pelvic fascia, lies a very poorly vascularized layer, where dissection is optimally performed. In this manner bleeding can be avoided, which would occur in a tubular resection, i.e. resection performed near the rectum.

More important, however, is the simultaneous removal of the so-called mesorectal fatty tissue, or mesorectum, including its locoregional lymph nodes.

This surgical step is called „total mesorectal excision“ or „partial mesorectal excision“, depending on the location of the rectal carcinoma removed. In a strict anatomic sense, the mesorectum is not “meso-“, since it does not involve a doubling of the peritoneum, through which organ supplying vessels run. Nevertheless, the term has become established internationally. The TME concept was introduced more than 20 years ago by RJ Heald3

Optimal surgical quality in TME depends on total resection of the mesorectal fatty tissue without cutting towards the tubular rectum during distal dissection. This so-called “coning” could leave behind lymph node metastases that worsen the patient’s prognosis.

The quality of the mesorectal excision is classified by the pathologist according to the M.E.R.C.U.R.Y. criteria as being good (1), intermediate, or poor (3).

References

- Survival after high or low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery during curative surgery for rectal cancer.Ann Surg. 1984 Dec;200(6):729-33.: Pezim ME, Nicholls RJ.

- Effect of high and intermediate ligation on survival and recurrence rates following curative resection of colorectal cancer.Dis Colon Rectum. 1997 Oct;40(10):1205-18; discussion 1218-9.: Slanetz CA Jr1, Grimson R.

- Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer.N Engl J Med. 2004 Oct 21;351(17):1731-40.:

- Adjuvant vs. neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: the German trial CAO/ARO/AIO-94.Colorectal Dis. 2003 Sep;5(5):406-15.Sauer R1, Fietkau R, Wittekind C, Rödel C, Martus P, Hohenberger W, Tschmelitsch J, Sabitzer H, Karstens JH, Becker H, Hess C, Raab R; German Rectal Cancer Group.

- Rectal carcinoma: is too much neoadjuvant therapy performed? Proposals for a more selective MRI based indicationZentralbl Chir. 2006 Aug;131(4):275-84.: Junginger T1, Hermanek P, Oberholzer K, Schmidberger H.Junginger T1, Hermanek P, Oberholzer K, Schmidberger H.

- Preoperative radiotherapy versus selective postoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer (MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG C016): a multicentre, randomised trial.Lancet. 2009 Mar 7;373(9666):811-20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60484-0.Sebag-Montefiore D1, Stephens RJ, Steele R, Monson J, Grieve R, Khanna S, Quirke P, Couture J, de Metz C, Myint AS, Bessell E, Griffiths G, Thompson LC, Parmar M.

- Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 14;355(11):1114-23.Bosset JF1, Collette L, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Radosevic-Jelic L, Daban A, Bardet E, Beny A, Ollier JC; EORTC Radiotherapy Group Trial 22921.

Wound Healing

Wound Healing Infection

Infection Acute Abdomen

Acute Abdomen Abdominal trauma

Abdominal trauma Ileus

Ileus Hernia

Hernia Benign Struma

Benign Struma Thyroid Carcinoma

Thyroid Carcinoma Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism Hyperthyreosis

Hyperthyreosis Adrenal Gland Tumors

Adrenal Gland Tumors Achalasia

Achalasia Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal Carcinoma Esophageal Diverticulum

Esophageal Diverticulum Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal Perforation Corrosive Esophagitis

Corrosive Esophagitis Gastric Carcinoma

Gastric Carcinoma Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic Ulcer Disease GERD

GERD Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric Surgery CIBD

CIBD Divertikulitis

Divertikulitis Colon Carcinoma

Colon Carcinoma Proktology

Proktology Rectal Carcinoma

Rectal Carcinoma Anatomy

Anatomy Ikterus

Ikterus Cholezystolithiais

Cholezystolithiais Benign Liver Lesions

Benign Liver Lesions Malignant Liver Leasions

Malignant Liver Leasions Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis Pancreatic carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma