Pancreatic Carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma has an overall poor prognosis. Because its early symptoms are inconspicuous, it is usually not diagnosed until an advanced stage, which makes an R0 resection difficult. R0 resection, however, represents the only truly effective therapy for pancreatic carcinoma, if left untreated life expectancy is only a few months.

The increasing incidence of pancreatic carcinoma in the Western industrialized nations is not due so much to lifestyle as to increasing life expectancy since the likelihood of developing pancreatic carcinoma increases dramatically with age.

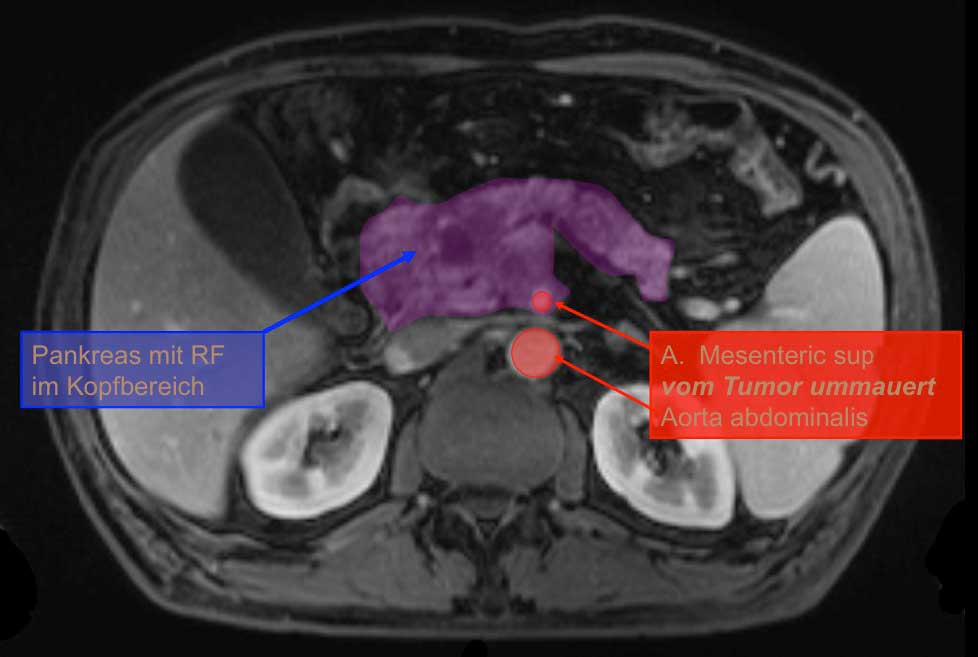

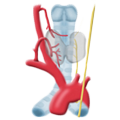

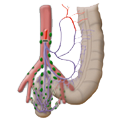

Pancreatic carcinomas can be divided into carcinomas of the pancreatic head, which at ca. 65% is the most frequent, carcinomas of the pancreatic body, and carcinomas of the pancreatic tail. The boundary between the pancreatic head and body runs at the level of the superior mesenteric artery, the pancreatic head begins at the left margin of the aorta.

Pancreatic carcinomas are to be distinguished from periampullary and papilla carcinomas, which occur in the area of the ampulla of Vater and have a much better prognosis than ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas.

Etiology

There are a number of risk factors for the development of pancreatic carcinomas, including alcohol and tobacco consumption, as well as obesity. Genetic factors also appear to play a role: the probability of pancreatic carcinoma, for example, is elevated in hereditary cancer syndromes like familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome, and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

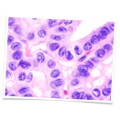

Diagnosis of pancreatic carcinomas is problematic since they remain so long asymptomatic. A consequence of this is the high proportion of affected lymph nodes and distant metastases at initial diagnosis. This is especially true of carcinomas of the pancreatic tail. In the pancreatic head, obstruction of the bile duct is more likely and thus a cholestasis, which then becomes symptomatic with a painless jaundice.

The classical clinical sign of pancreatic carcinoma is the Courvoisier sign, i.e. painless jaundice combined with an enlarged gallbladder. In contrast, an inflamed gallbladder with hydrops causes extreme pain.

Diagnosis of pancreatic carcinomas is problematic since they remain so long asymptomatic. A consequence of this is the high proportion of affected lymph nodes and distant metastases at initial diagnosis. This is especially true of carcinomas of the pancreatic tail. In the pancreatic head, obstruction of the bile duct is more likely and thus a cholestasis, which then becomes symptomatic with a painless jaundice.

The classical clinical sign of pancreatic carcinoma is the Courvoisier sign, i.e. painless jaundice combined with an enlarged gallbladder. In contrast, an inflamed gallbladder with hydrops causes extreme pain.

Therapy

The prognosis for pancreatic carcinoma remains poor. Untreated, life expectancy for patients with pancreatic carcinoma is only a few months. Only total surgical resection (R0 resection) brings major improvement in prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of about 40%.1

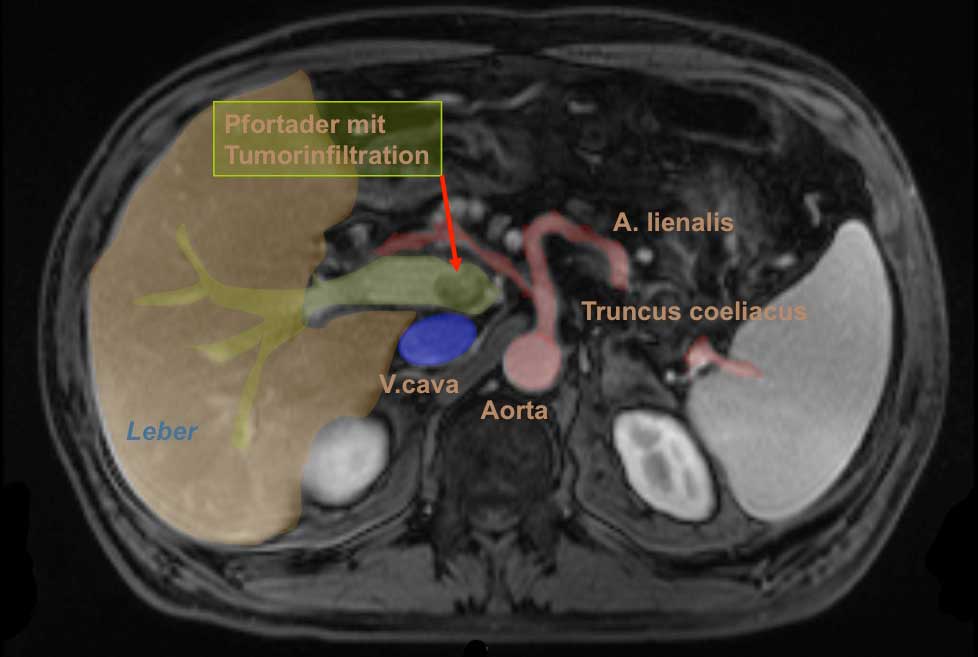

R0 resection is difficult to achieve because at initial diagnosis pancreatic carcinoma is often already advanced, with early metastases and prognostically unfavorable early infiltration of the perineural sheaths up to the retroperitoneum. At surgical exploration a peritoneal carcinosis is often found which was not evident at staging diagnosis.

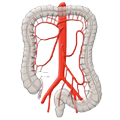

The choice of surgical procedure depends on the tumor’s location. Carcinomas in the pancreatic tail are treated by pancreas left resection, which includes splenectomy and systematic lymphadenectomy.

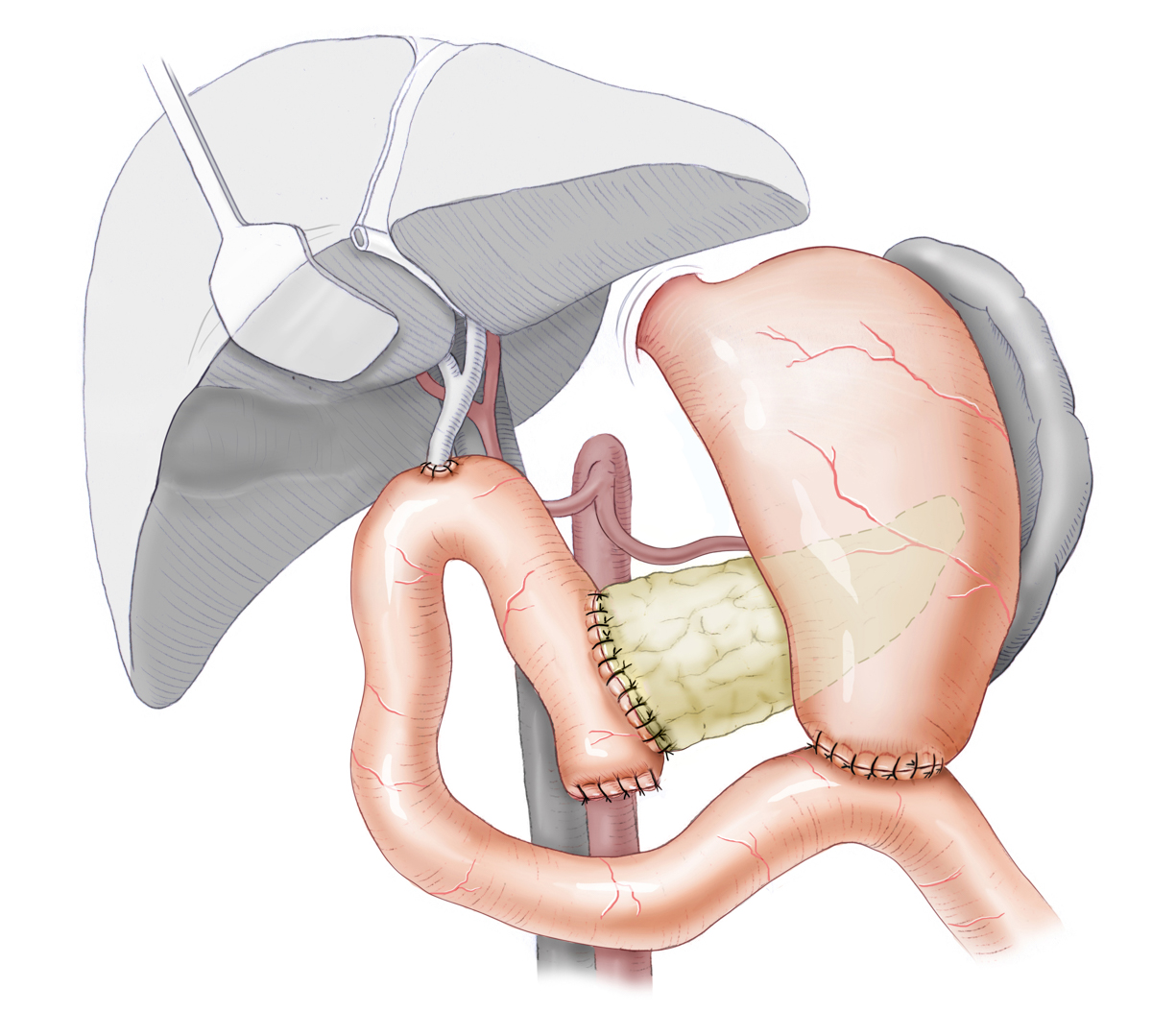

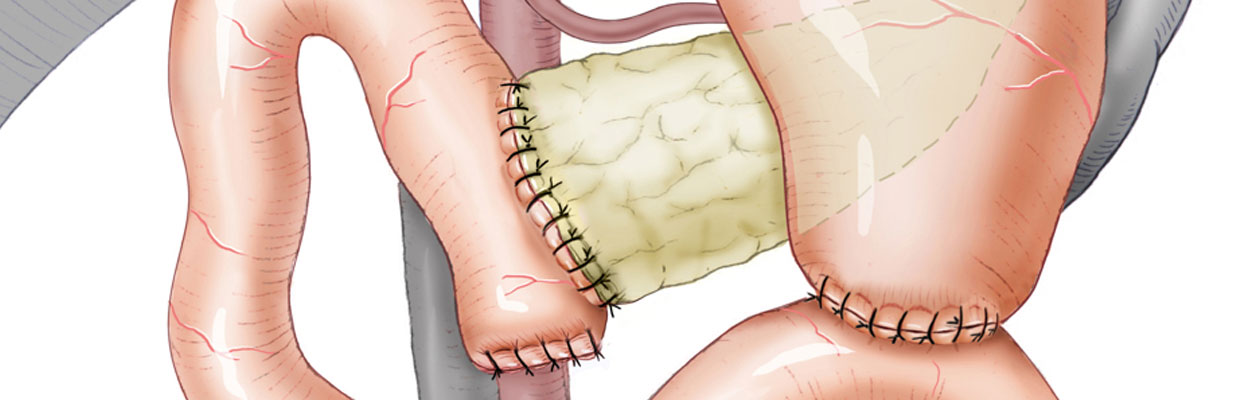

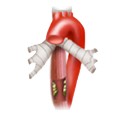

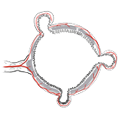

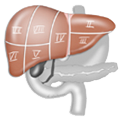

Pancreatic carcinoma of the pancreatic head is treated by a partial pancreaticoduodenectomy. Its classic variant with resection of the gastric antrum is termed the Kausch-Whipple procedure, or the Whipple-Op. In this procedure, the gallbladder, the distal portion of the bile duct, the duodenum, and naturally the pancreatic head are all removed. Reconstruction is then done with a pancreaticojejunostomy, hepaticojejunostomy, and gastrojejunostomy, usually as Y-Roux reconstruction.

At one time the gastric antrum was resected not for oncological reasons but because anastomosis of the stomach with the small intestine regularly led to severe ulceration in the latter. Then proton pump inhibitors were introduced that could prevent this. Today the gastric antrum is no longer resected, which improves the long-term quality of life and may reduce the morbidity of the procedure. Resection is only still done for very large tumors whose infiltration of the gastric antrum is questionable.

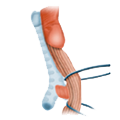

If the gastric antrum is preserved, this is called the Traverso-Longmire procedure. The resection volume is usually identical to that of the Whipple procedure. Clinically, this is also known as pylorus-preserving Whipple, or pp-Whipple. The pylorus is preserved and the duodenum resected immediately post-pyloric. The procedure does not have oncological drawbacks, but gastric emptying is better over long-term course if the pylorus is preserved because it prevents the dumping syndrome associated with gastric surgery.

Reconstruction after Whipple-Procedure

References

- One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies.Ann Surg. 2006 Jul;244(1):10-5.: Cameron JL1, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA.

Wound Healing

Wound Healing Infection

Infection Acute Abdomen

Acute Abdomen Abdominal trauma

Abdominal trauma Ileus

Ileus Hernia

Hernia Benign Struma

Benign Struma Thyroid Carcinoma

Thyroid Carcinoma Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism Hyperthyreosis

Hyperthyreosis Adrenal Gland Tumors

Adrenal Gland Tumors Achalasia

Achalasia Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal Carcinoma Esophageal Diverticulum

Esophageal Diverticulum Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal Perforation Corrosive Esophagitis

Corrosive Esophagitis Gastric Carcinoma

Gastric Carcinoma Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic Ulcer Disease GERD

GERD Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric Surgery CIBD

CIBD Divertikulitis

Divertikulitis Colon Carcinoma

Colon Carcinoma Proktology

Proktology Rectal Carcinoma

Rectal Carcinoma Anatomy

Anatomy Ikterus

Ikterus Cholezystolithiais

Cholezystolithiais Benign Liver Lesions

Benign Liver Lesions Malignant Liver Leasions

Malignant Liver Leasions Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis Pancreatic carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma