Introduction

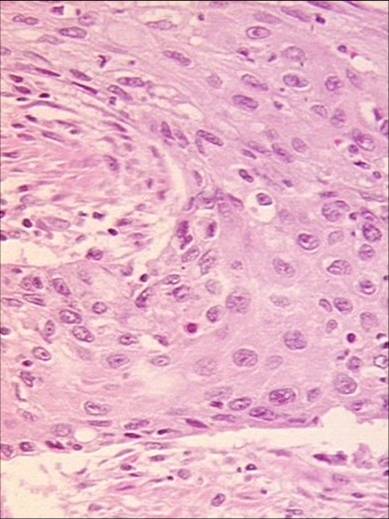

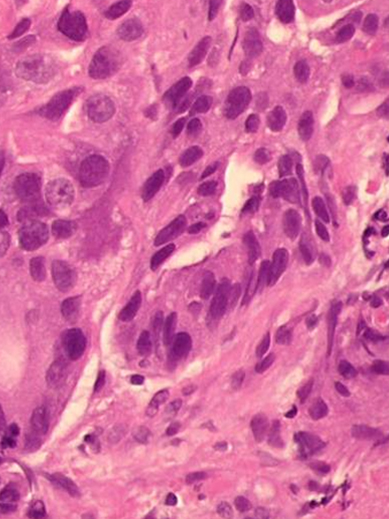

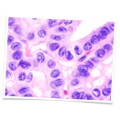

There are two main histological types of malignant epithelial tumors of the esophagus: Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. These two entities differ with regard to etiology, pathogenesis, and localization. The more common of the two is squamous cell carcinoma, although adenocarcinoma is increasing dramatically in incidence, especially is the Western world. Much less common are mesenchymal tumors like leiomyosarcoma.

The prognosis for malignant epithelial tumors of the esophagus is on the whole poor, since many at diagnosis already show lymphogenous metastasis. This is facilitated by the very good lymphatic drainage of the esophagus and means that the probability of affected lymph nodes increases even after very shallow tumor invasion of the esophageal wall. This has an immediate adverse effect on overall prognosis and limits the effectiveness of local procedures that resect the mucosa but leave the lymph nodes.

Localization

The esophagus is normally lined with squamous epithelium in contrast to the columnar epithelium of the stomach. Squamous cell carcinomas can therefore occur along the entire length of the esophagus. In up to 15% of cases they occur at multiple sites in the esophagus, which is almost never true of adenocarcinomas.

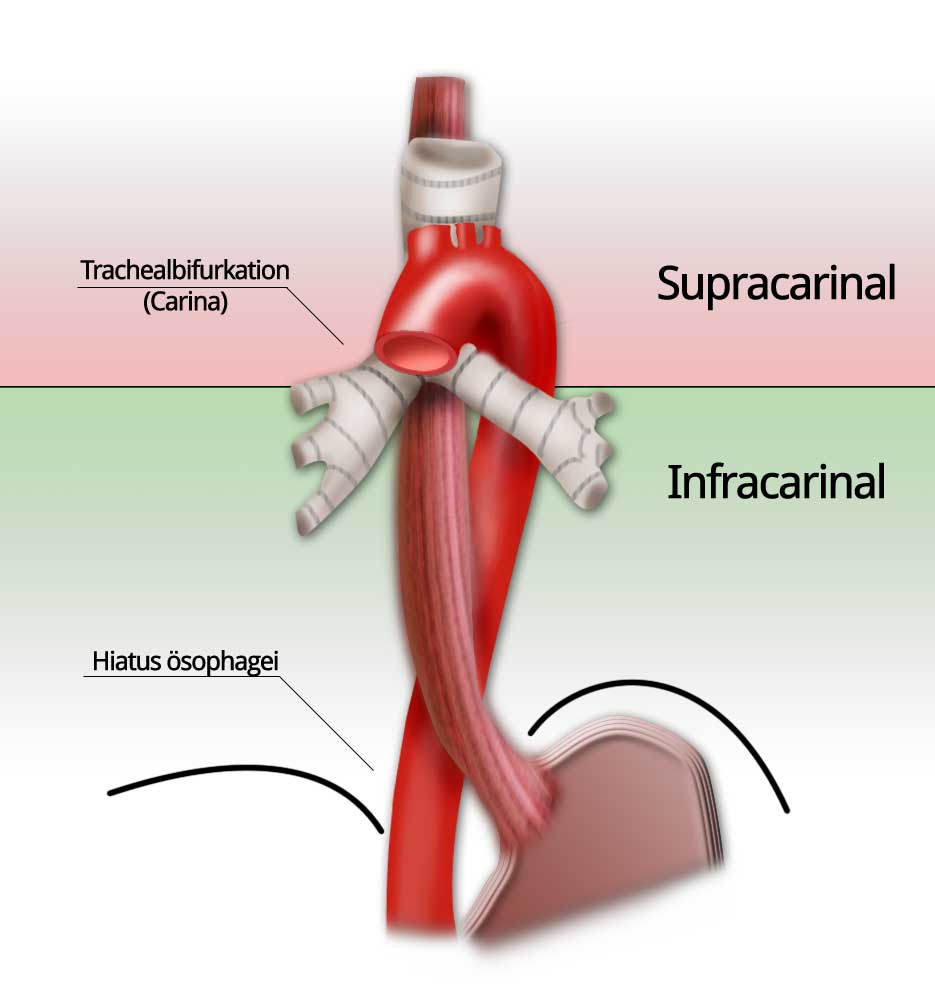

Due to the close proximity of squamous cell carcinomas to the tracheobronchial system, their localization is classified relative to the tracheal bifurcation, the carina. This is a relatively uniform anatomic landmark and thus represents a useful classification. Infracarinal tumors have a prognostic advantage in not being located so close to the tracheobronchial system and thus being better candidates for primary resection. The close proximity of supracarinal and cervical tumors to the trachea and the left main bronchus impedes radical surgery.

Adenocarcinomas, by contrast, are located almost exclusively in the distal esophagus. They originate in a mucous membrane with dysplastic changes due to persistent gastroesophageal reflux, which explains their exclusive origin in the distal esophagus.

Etiology

The etiologies of squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas are very different. Squamous cell carcinomas are closely linked with nicotine and alcohol abuse as well as consumption of food containing nitrosamines. They are also described in patients with corrosive esophageal stricture and achalasia. In up to 10% of patients with squamous cell carcinomas of the esophagus two tumors are found in the ears, nose, and throat (ENT) region.

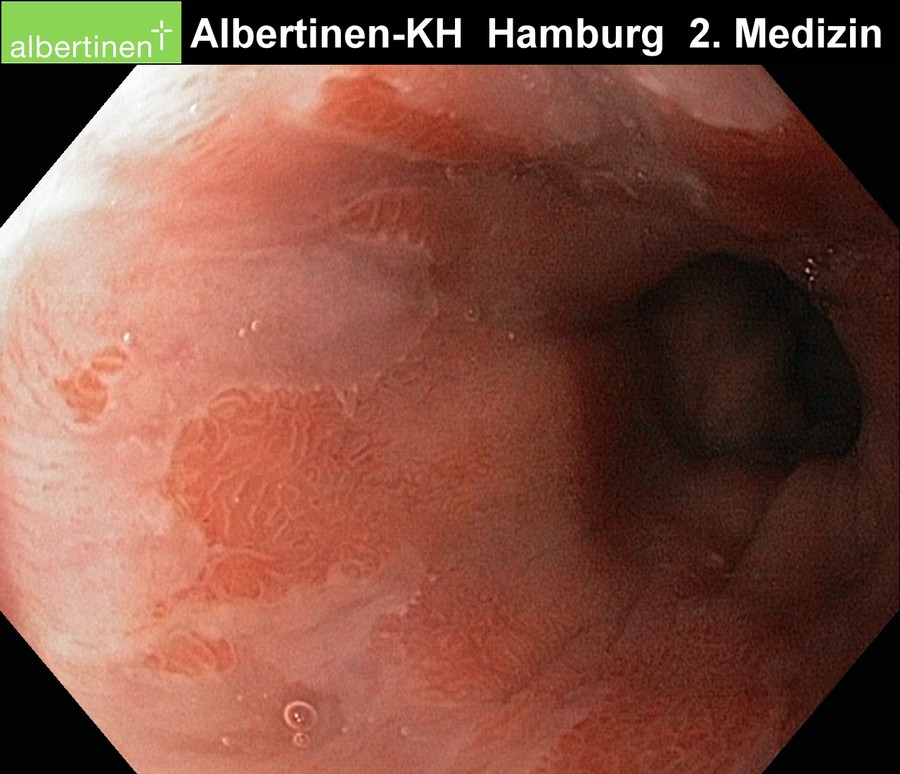

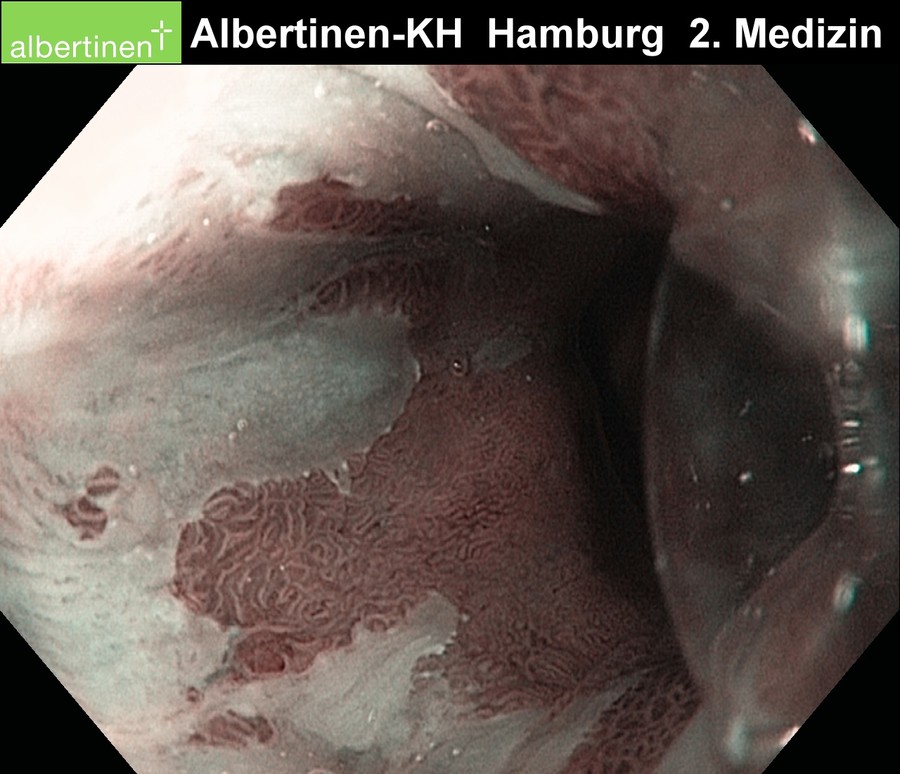

Up to 90% of adenocarcinoma patients are found to have Barrett’s esophagus. The carcinogenesis is facilitated by a chronic reflux esophagitis, which can lead to Barrett’s metaplasia, where the stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus transforms into simple columnar epithelium. Because the esophagus is effectively shortened by the upward growth of the intestinal mucousa, one speaks in Germany of endobrachyoesophagus. The synonymous term Barrett’s esophagus, however, is more common. A distinction is made between short-segment Barrett’s (≤ 3cm) and long-segment Barrett’s (4-10cm).

As a rule of thumb about 10% of patients with chronic reflux develop Barrett’s metaplasia, and about 10% of these risk developing an invasive Barrett’s esophagus (cancer). The efficacy of antireflux surgery in preventing this development is questionable. It may be that the indication for this surgery is made too late, in any case once metaplastic changes occur they cannot be reversed1

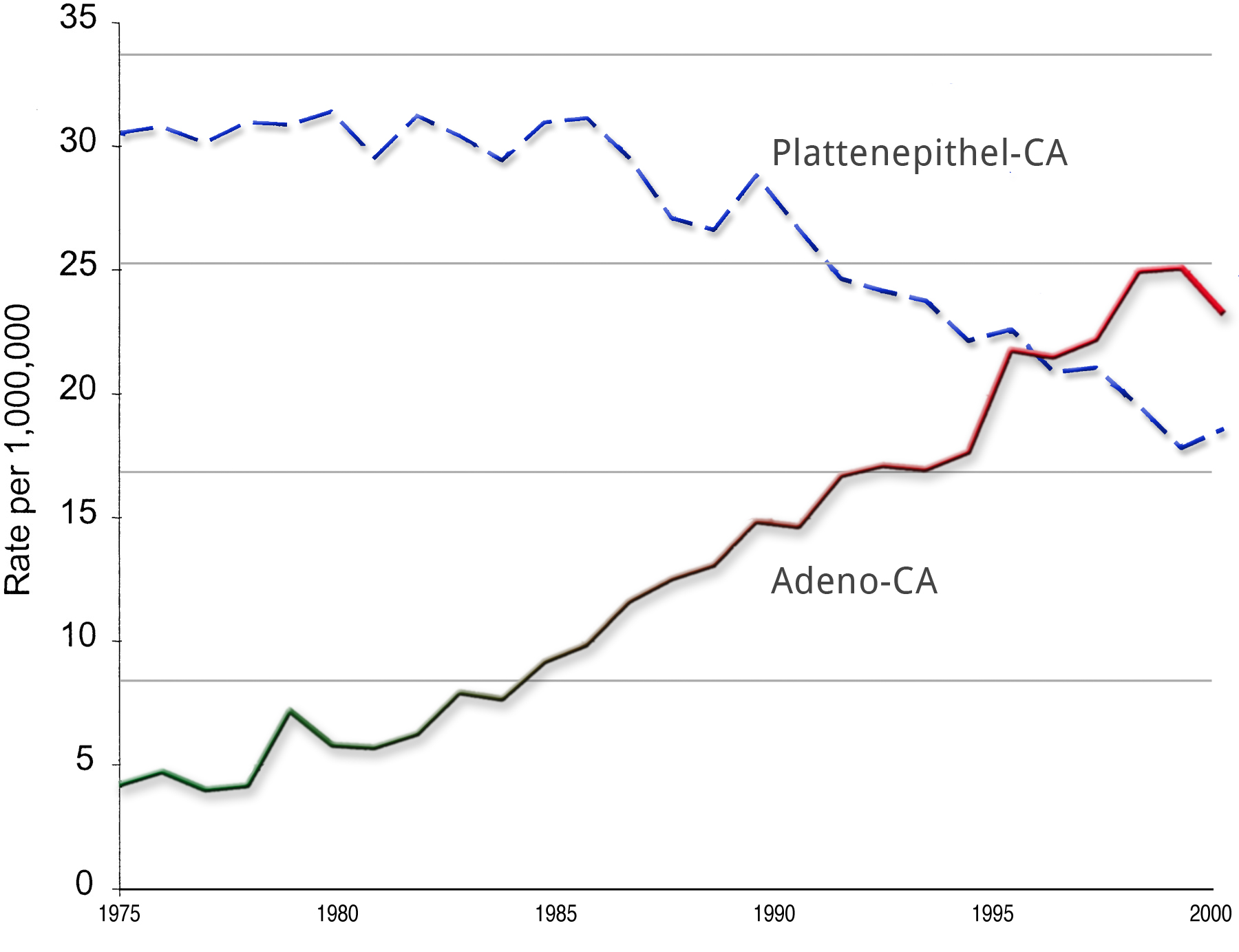

Incidence

In recent years and decades, the incidence of adenocarcinoma has risen dramatically, especially in the Western world. If 40 years ago an adenocarcinoma of the esophagus was an absolute rarity, its incidence today sometimes surpasses that of squamous cell carcinoma.2

Why this has occurred is not fully understood. It could be due to changes in lifestyle and diet, or perhaps merely to improved diagnosis.

Original Article

If you are interested in reading more on the increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma, try the following article by Pohl and Welch in PubMed: The role of over diagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence.

Dysphagia:

The main symptom of esophageal carcinoma

Symptoms

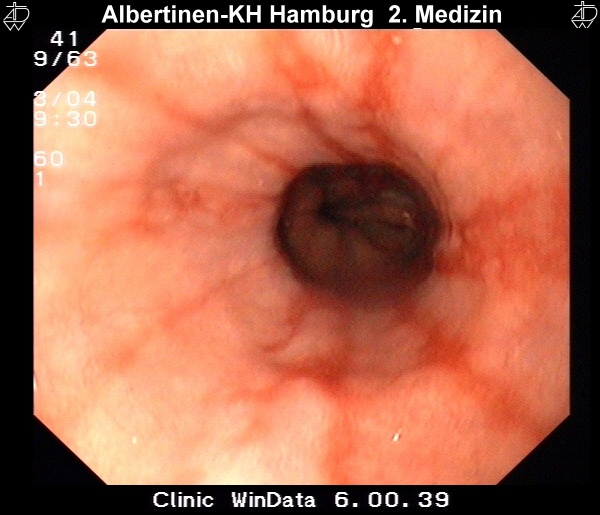

Unfortunately, esophageal carcinoma has no early symptoms. The majority of patients report difficulty in swallowing, i.e. dysphagia, which usually first occurs when about 2/3 of the esophageal lumen is occluded. Dysphagia is thus a late symptom of esophageal carcinoma.

Since this is usually the only symptom, it is termed presenting symptom dysphagia. This is of course a nonspecific symptom and the list of differential diagnostic possibilities is long. Nevertheless, dysphagia must always be evaluated with an eye to a possible malignancy.

Differential diagnoses Dysphagie

- Achalasia

- Zenker's diverticulum

- Peptic stenosis

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

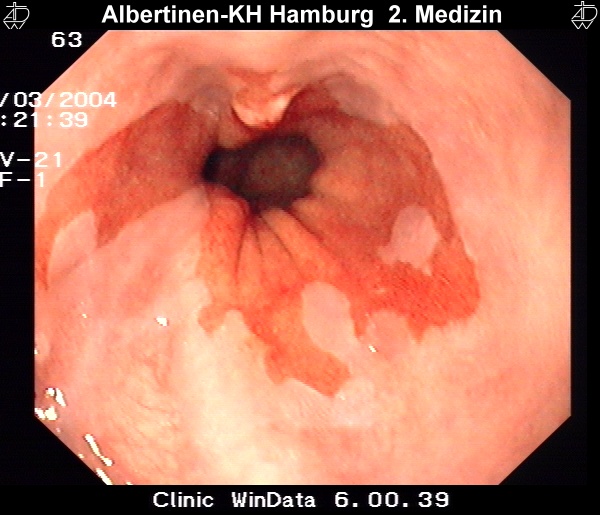

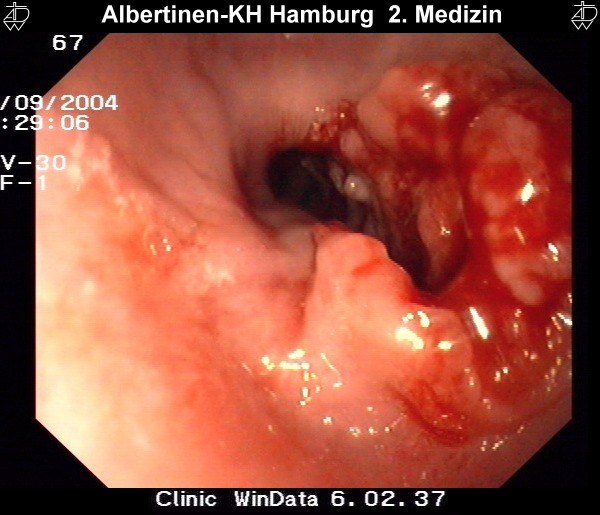

Sample images from endoscopy

courtesy of Albertinen-Krankenhaus Hamburg

Other symptoms include weight loss, globus sensation, regurgitation, and retrosternal pain. A palpable tumor or lymph node as well as hoarseness may indicate an advanced finding Considering the lack of reliable early findings and the excellent lymphatic drainage of the esophagus (drainage begins just under the mucosa), it is no wonder that many patients exhibit lymph node metastasis at initial diagnosis.

Because the complaints of patients are often nonspecific and may point in the wrong direction, diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is frequently an incidental finding. Adenocarcinomas are also commonly diagnosed in the context of surveillance programs involving regularly repeated biopsies in patients with known Barrett’s esophagus. In keeping with the pathogenesis, such surveillance programs appear to make sense not only for Barrett’s esophagus patients, but also for patients with long-term achalasia, caustic strictures, or squamous cell carcinoma in the ENT region.

Risk analysis

In keeping with its etiology, patients with esophageal carcinoma generally suffer from numerous accompanying diseases. The main risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma are long-term nicotine and alcohol abuse. Liver function status and the likelihood of postoperative alcohol consumption are factors that must be weighed when deciding whether to risk surgical intervention.

Postoperative alcohol withdrawal delirium increases the lethality of intervention by about 50%!

Manifest cirrhosis of the liver also dramatically worsens outcome. This can sometimes be difficult to diagnose, all available means should be used to achieve clarification, in doubtful cases by means of liver biopsy. Patients with squamous cell carcinoma are often under- or malnourished, a condition that needs to be recognized and treated early and/or must be taken into account when choosing a therapeutic strategy. Obstructive pulmonary disease, which often accompanies squamous cell carcinoma, can be easily diagnosed by a pulmonary function test. This should definitely be done before a possible thoracotomy.

Patients with adenocarcinoma are usually overweight and have coronary heart disease. Priority should be given in these patients to checking cardiovascular risk factors.

Patient compliance is also a factor in assessing risk. For better comparability, various scoring systems have been developed that put the choice of therapy on as objective a basis as possible.3

| SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA | ADENOCARCINOMA |

|---|---|

| Alcohol abuse | Coronary heart disease |

| Nicotine | Übergewicht |

| COPD | GERD |

| Liver dysfunction | |

| Malnutrition |

Simplified risk scoring system44

(nach Bartels et al 1998)

| Parameter | PREOPERATIVE SCORE | WEIGHTING FACTOR | Minimum Score | Maximum Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENERAL HEALTH | 1-2-3 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| CARDIAC FUNCTION | 1-2-3 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| LIVER FUNCTION | 1-2-3 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| PULMONARY FUNCTION | 1-2-3 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| SUM | 11 | 33 |

1= normal 2=slight limitation 3=severe limitation

A total score of 21 or above is associated with a clearly elevated risk, the OP indication should be very strictly applied.

Diagnose & Staging

Endoscopy

Diagnostikmethode der ersten Wahl.

- Biopsy

- Distance to anterior teeth

- Relation to gastro-esophageal junction

Barium fluoroscopy

Typical changes are also evident in barium fluoroscopy of the esophagus. A shadow in barium fluoroscopy or a stricture suggest a locally advanced tumor.

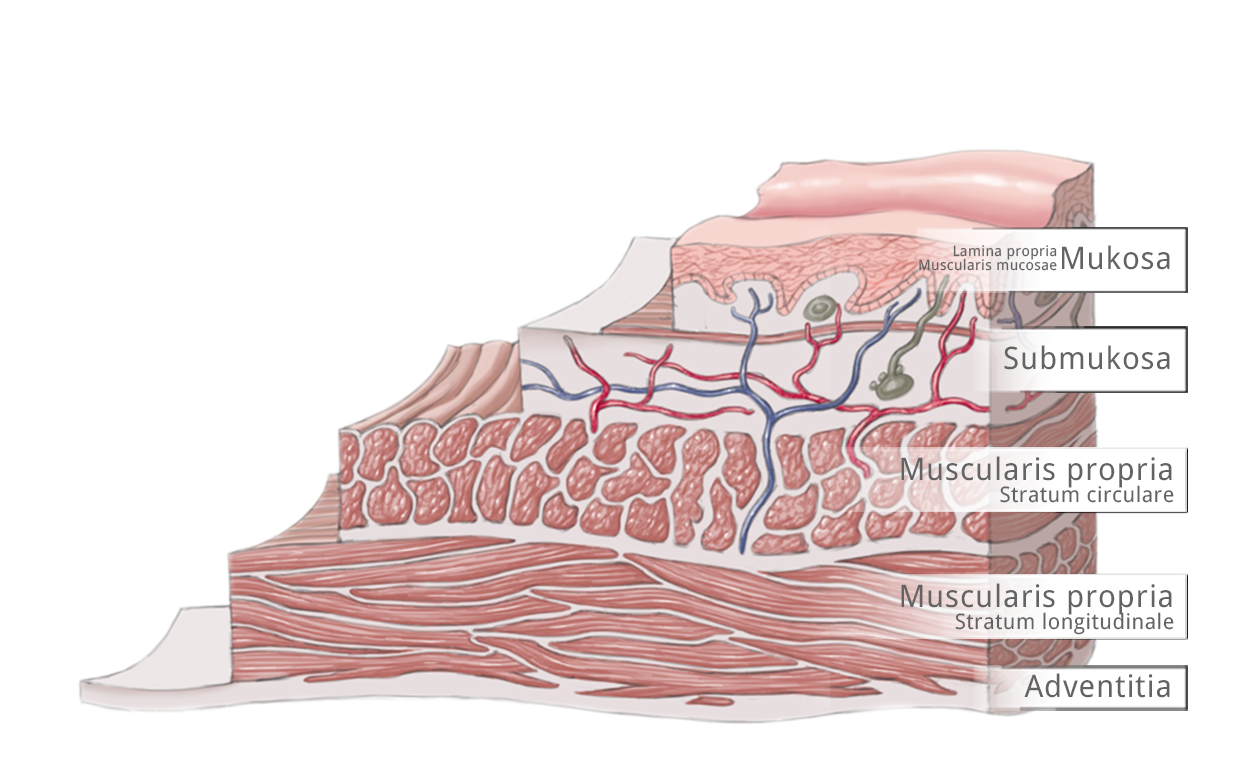

Endosonography

Endosonography can be used for local staging and to estimate the depth of invasion of the esophageal wall. It may also be able to detect affected lymph nodes.

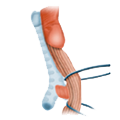

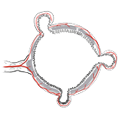

The esophageal wall is comprised of the mucosa with lamina propria and lamina muscularis mucosae, tela submucosa, tunica muscularis with circular and longitudinal layers, and the tunica adventitia. These are bordered by the neighboring structures of the esophagus.

According to the TNM classification, T1a tumors invade the mucosa up to the lamina muscularis mucosae and T1b tumors invade the submucosa. Three depths of invasion are distinguished, T2 tumors invade the muscularis, T3 the adventitia, and T4 tumors invade adjacent structures.

Staging

Esophageal carcinomas are classified according to the guidelines of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). Squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas differ with regard to the probability of lymph node metastasis. Whereas the former exhibit a higher rate, with very early metastasis after shallow invasion, adenocarcinomas have a lower rate. This lower rate may be explained by obstruction of the lymphatic pathways due to chronic inflammation secondary to longterm reflux esophagitis.

TNM 7 2009 – German edition 2010

Optional Examination

-

- Bronchoskopy to rule out esophagobronchial fistula

- Staging-Laparoskopy to rule out pertioneal carcinomatosis

- Risk-analysis

- tumour marker in the follow up (squamous cell carcinoma : SCC, Adenocarcinoma: CEA)

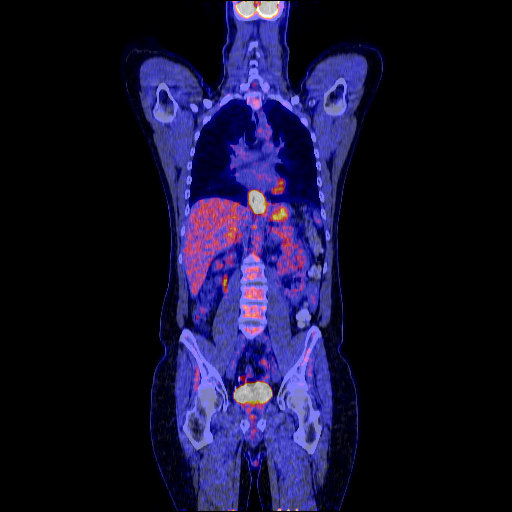

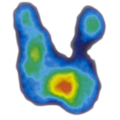

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET

FDG PET scans when combined with CT offer enhanced precision in the detection of affected lymph nodes or distant metastases.5

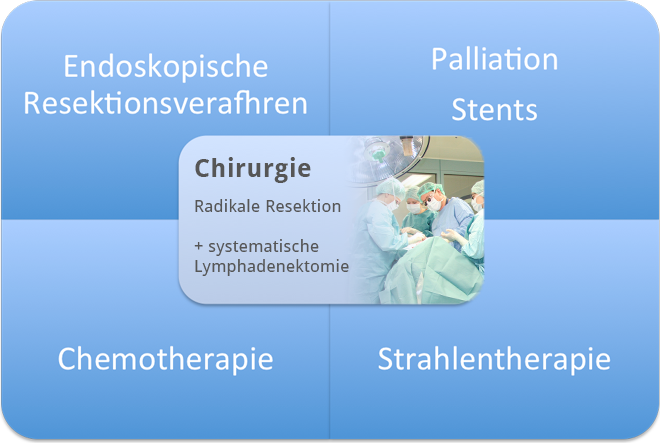

Multimodality Therapy

The step in esophageal carcinoma therapy that most affects prognosis is radical surgical resection with systematic lymph node dissection. This was already recognized by Theodor Billroth in 1890, who stated that "Treatment of esophageal carcinoma belongs in the hands of the surgeon."

Still, treatment of esophageal carcinoma today is rooted in multimodality concepts where radiation and chemotherapy play as important a role as endoscopic procedures

Locally RESECTABLE

"Technical Operability"

No distant metastases

Basic Requirements

Every surgical measure in esophageal carcinoma must be predicated on two basic considerations: Can the tumor be resected (i.e. is it technically possible to completely remove it) and is the patient healthy enough survive surgery. In addition to the technical feasibility of surgery there is the functional operability. Because patients with squamous cell carcinoma in especially likely of suffer from severe accompanying diseases, assessment of risk is of paramount importance. Risk can be assessed using scoring systems that take into account the patient’s cardiopulmonary situation and such other factors as compliance.

PATIENT OPERABLE

"Functional Operability"

Risk analysis

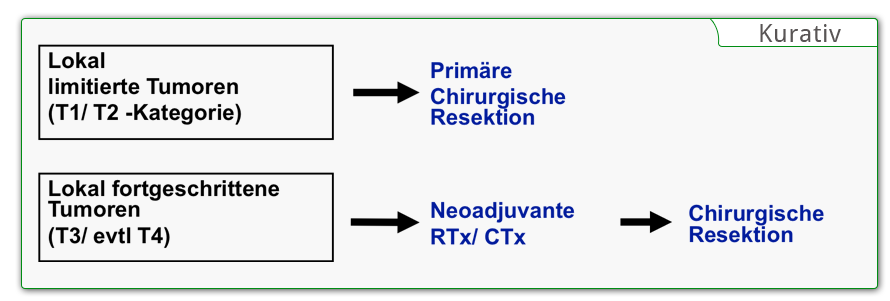

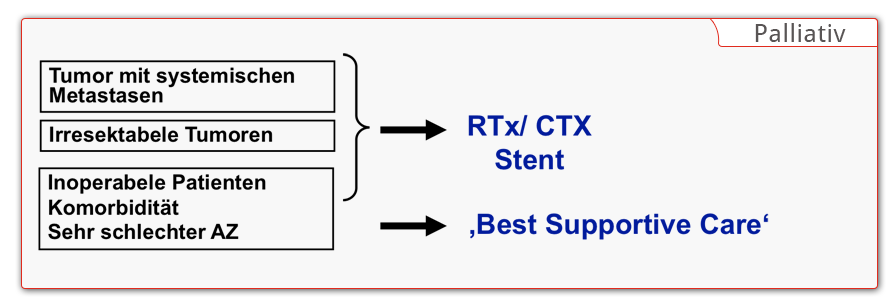

Stage-Adapted Therapy

Complete removal of the tumor is the goal of every surgical intervention in esophageal carcinoma. If primary R0 resection does not appear feasible in locally advanced tumors, neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiochemotherapy is used. Depending on the effectiveness, it may be possible to achieve secondary resectability. During restaging, the tumor’s response to the neoadjuvant treatment is clarified. If the patient is functionally inoperable, definitive radiotherapy and/or radiochemotherapy is performed. In patients with nonresectable tumors or with distant metastases, palliative therapy offering the “best supportive care” is given.

Locally limited resection is reserved for the very early stages of adenocarcinoma. Already with invasion of the submucosa the risk of lymph node metastases rises dramatically, meaning that endoscopic mucosal resection does offer sufficient radicality. In squamous cell carcinomas, locally limited therapy is also ruled out because they often develop into longitudinal submucosal lymphangitic carcinomatosa.

Surgical Therapy

The goal of surgical treatment of esophageal carcinoma is subtotal resection of the esophagus and removal of the regional lymph nodes. An exception is early stages of adenocarcinomas, where limited resection of the distal esophagus and the gastroesophageal junction can be justified. For in-situ carcinomas, endoscopic mucosal resection is an option if it is borne in mind that even shallow submucosal invasion is associated with lymph node metastasis, after which sufficient radicality is no longer possible.

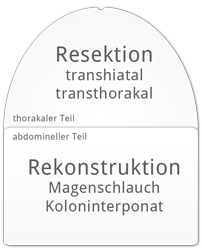

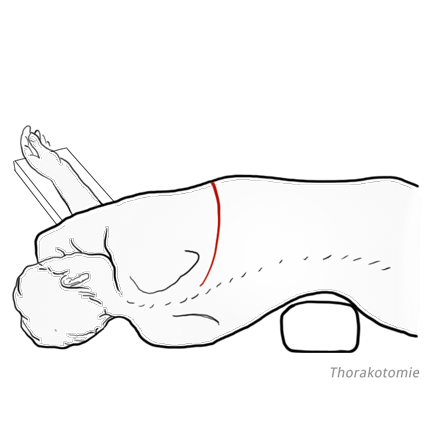

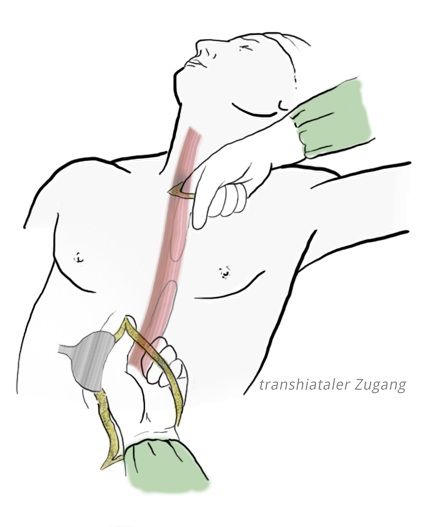

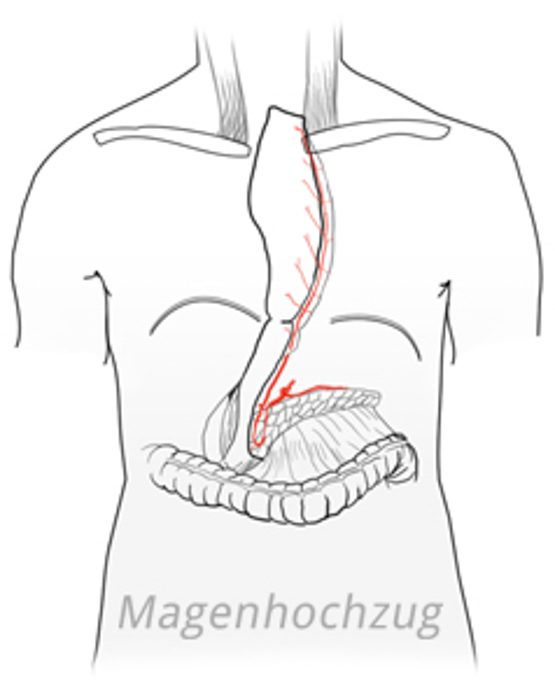

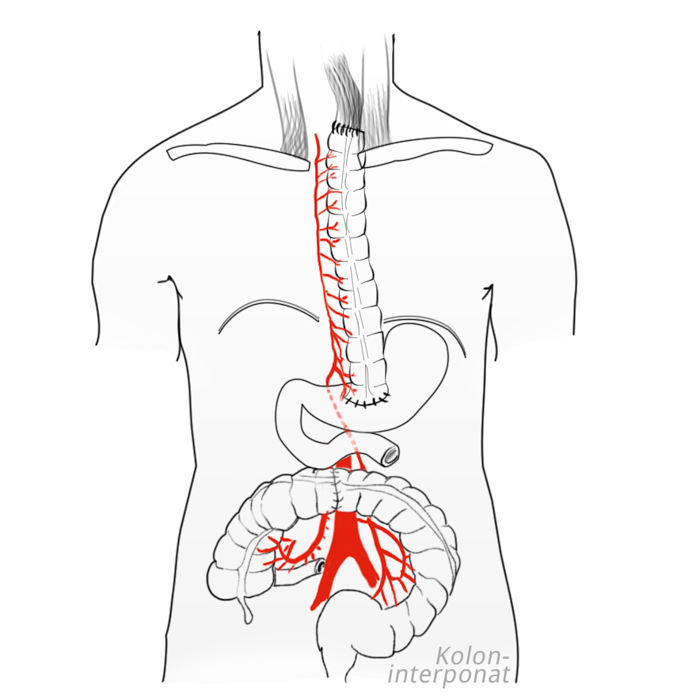

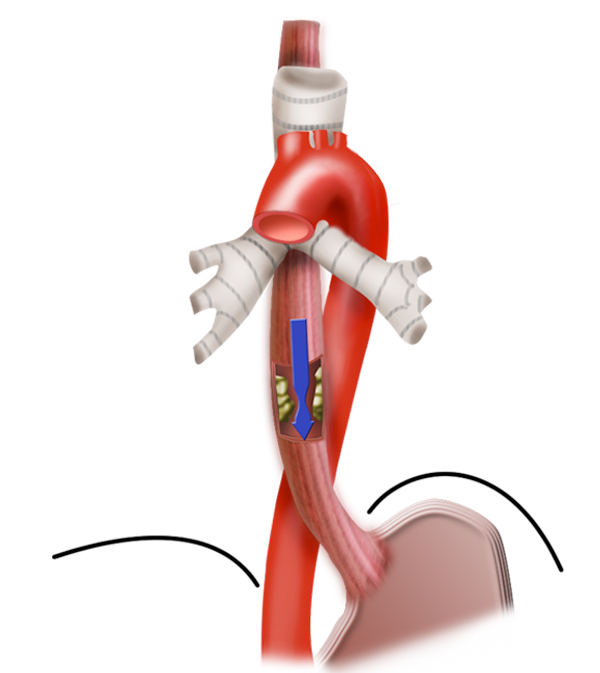

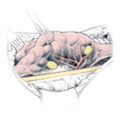

Resection is followed by reconstruction of the esophagus. A number of techniques are available for this purpose, including using a stomach tube or colon interposition to replace the esophagus. Esophageal carcinoma surgery is therefore a “double lumen procedure,” in which resection is performed in the thorax, reconstruction in the abdomen. Thoracotomy is particular harbors a not inconsiderable risk of morbidity for patients with prior cardiopulmonary disease. To lessen the risk for these patients, the esophagus can be resected without thoracotomy by bluntly shucking the esophagus from the mediastinum with a finger.

Transhiatal esophagectomy

In this procedure dissection is performed abdominally using a transhiatal access. With an additional cervical incision the blunt dissection is completed. This helps especially to avoid postoperative pulmonary complications. However, the accompanying lymphadenectomy is not possible to the same extent, so that here compromises must be made.

While the extent of the abdominal lymphadenectomy is identical in both procedures, in the transhiatal access fewer thoracic lymph nodes are removed. This possibly also accounts for the poorer overall survival in patients who have undergone transhiatal resection.

6,7

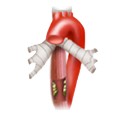

Surgical Safety

To ensure surgical safety, a two-step approach can be used in patients who have undergone preoperative radio- or chemotherapy. The first step involves resection of the right thoracic esophagus with mediastinal lymphadenectomy, the second step is reconstruction. This takes place no earlier than a week later to allow time for sufficient adhesion of the posterior mediastinum, so that even in the event of anastomotic insufficiency a life-threatening mediastinitis is unlikely. The patient is fed during this period through a temporary percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, i.e. via a feeding tube introduced through the abdominal wall and into the stomach.

Reconstruction

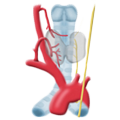

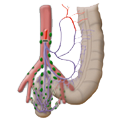

A number of methods are available for reconstructing the defect created by esophageal resection. In gastric pull-up, a thin stomach tube is formed with a stapler. The large curvature is preserved intact and the stomach tube is supplied with blood by the right gastroepiploic artery.

To determine whether the colon can be used for colonic interposition, colonoscopy should be performed prior to esophageal resection so as to exclude any pathologies in this region. The transverse colon is just as suited for colonic interposition as the right hemicolon.

The esophagus can be reconstructed in its original bed, i.e. mediastinal. This offers better postoperative swallowing function. Alternatively, the colonic interposition can be pulled up extra-anatomically retrosternal or even antesternal, which especially makes sense if follow-up radiotherapy is planed. The anastomosis can be made with hand sutures or a stapler. It can be placed cervical or intrathoracic, which is the established international standard.

References

- The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma after antireflux surgery.

Gastroenterology. 2010 Apr;138(4):1297-301. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.004. Epub 2010 Jan 18.Lagergren J, Ye W, Lagergren P, Lu Y. - The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence.J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Jan 19;97(2):142-6.Pohl H, Welch HG.

- Risk analysis in esophageal surgery.Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;155:89-96.Bartels H, Stein HJ, Siewert JR.

- Preoperative risk analysis and postoperative mortality of oesophagectomy for resectable oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998 Jun;85(6):840-4.Bartels H, Stein HJ, Siewert JR.

- The incremental effect of positron emission tomography on diagnostic accuracy in the initial staging of esophageal carcinoma.Cancer. 2005 Jan 1;103(1):148-56.Kato H, Miyazaki T, Nakajima M, Takita J, Kimura H, Faried A, Sohda M, Fukai Y, Masuda N, Fukuchi M, Manda R, Ojima H, Tsukada K, Kuwano H, Oriuchi N, Endo K.

- Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.N Engl J Med. 2002 Nov 21;347(21):1662-9.Hulscher JB1, van Sandick JW, de Boer AG, Wijnhoven BP, Tijssen JG, Fockens P, Stalmeier PF, ten Kate FJ, van Dekken H, Obertop H, Tilanus HW, van Lanschot JJ.

- Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the mid/distal esophagus: five-year survival of a randomized clinical trial.Ann Surg. 2007 Dec;246(6):992-1000; discussion 1000-1.Omloo JM1, Lagarde SM, Hulscher JB, Reitsma JB, Fockens P, van Dekken H, Ten Kate FJ, Obertop H, Tilanus HW, van Lanschot JJ.

Wound Healing

Wound Healing Infection

Infection Acute Abdomen

Acute Abdomen Abdominal trauma

Abdominal trauma Ileus

Ileus Hernia

Hernia Benign Struma

Benign Struma Thyroid Carcinoma

Thyroid Carcinoma Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism Hyperthyreosis

Hyperthyreosis Adrenal Gland Tumors

Adrenal Gland Tumors Achalasia

Achalasia Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal Carcinoma Esophageal Diverticulum

Esophageal Diverticulum Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal Perforation Corrosive Esophagitis

Corrosive Esophagitis Gastric Carcinoma

Gastric Carcinoma Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic Ulcer Disease GERD

GERD Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric Surgery CIBD

CIBD Divertikulitis

Divertikulitis Colon Carcinoma

Colon Carcinoma Proktology

Proktology Rectal Carcinoma

Rectal Carcinoma Anatomy

Anatomy Ikterus

Ikterus Cholezystolithiais

Cholezystolithiais Benign Liver Lesions

Benign Liver Lesions Malignant Liver Leasions

Malignant Liver Leasions Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis Pancreatic carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma